The Speech That Applauded Itself

Why Mark Carney’s Davos Address Impressed Everyone—And Said Almost Nothing

Was That Really a Great Speech?

The reaction to Mark Carney’s Davos speech tells us far more about Canada than it does about Mark Carney.

The speech was widely praised as “serious,” “statesmanlike,” even “historic.” But if one asks the simplest possible question—what, precisely, was said?—The applause quickly dissolves into mist. Strip away tone, cadence, vibe, “hope-inspiring,” and the other euphemisms that flatter without informing, and insist on something more basic:

Which idea in this speech was genuinely new, concrete, and likely to materially improve the lives of ordinary Canadians?

At that point, most admirers would begin checking their phones, answering imaginary messages, or suddenly remembering an urgent need to refresh their drink. This is not because they are dishonest, but because they have been trained to confuse fluency with substance. They know how the speech made them feel; they cannot say what it proposed.

I read the speech slowly. Line by line. Without the music, without the applause, without the glow of Davos or the flattering summaries of the press. I wonder how many others did the same. Because when you do, something awkward becomes apparent: beneath the polish, the metaphors, and the borrowed gravitas, there is remarkably little there that is new, specific, risky, or accountable. There are many internal contradictions.

That, of course, is not a failure of technique. It is the technique.

Mark Carney has perfected a particular political art: offering just enough rhetorical nourishment to whet the appetite while ensuring the banquet never arrives. One leaves the table satisfied in mood but unchanged in circumstance—still hungry, still waiting, still applauding.

That is not an accident. It is the method.

I. The Art of Saying Nothing Beautifully

There is nothing new about electorates mistaking polish for substance. History is crowded with societies that confused fluency with wisdom and charm with competence.

What is new today is the speed and shallowness of the seduction. Modern politics has absorbed the full logic of branding. Leaders are marketed as consumables; citizens are treated as customers—distractible, impatient, and easily reassured. Governance becomes a branch of public relations.

If Carney were truly invoking Thucydides rather than merely decorating his speech with him, the argument would be brutally direct. He would say that power, not sentiment, structures the world; that small and middle powers survive by anchoring themselves to a dominant ally; and that provoking the hegemon on whom one depends while flirting with an authoritarian rival is not independence but folly.

Thucydides1 would say, "Beware, China, you idiot Carney.”

He would acknowledge that alliances impose discipline, that sovereignty is constrained by reality, and that words unsupported by leverage invite punishment.

Instead, Carney offers a stage-managed counterfeit. His speech is smooth, camera-ready, and exquisitely managed, but empty of the intellectual burden his references imply. It gestures at history—Thucydides here, Havel there—without allowing either to impose cost. Quotations are used as incense, not as obligations.

The result is not realism but evasion: moral language without strategy, posture without alignment, and a reckless willingness to antagonise the United States while remaining studiously vague about the dangers of dependence on China. The references flatter the audience while demanding nothing of the speaker—and excuse a course of action that Thucydides himself would have regarded as suicidal.

We are told that the “rules-based international order” was a pleasant fiction that is now collapsing. This sounds bracingly realistic until one asks the obvious question: a fiction compared to what? The post-1945 order—however imperfect—was anchored in American military, economic, and institutional dominance. NATO, Bretton Woods, open sea lanes, deterrence against expansionist powers: these were not illusions. They were enforced realities, underwritten largely by the United States, often while its allies moralised, freeloaded, and complained.

To call this a “fiction” is not realism. It is ingratitude with a thesaurus.

Carney never acknowledges the central historical fact that Conrad Black correctly emphasises: the Western alliance contained and ultimately outlasted the Soviet Union without a direct NATO–Warsaw Pact war—an extraordinary civilisational achievement. What has changed is not the unreality of that order, but America’s patience with underwriting it alone.

Yet instead of confronting this directly, Carney offers abstractions: “middle powers,” “variable geometry,” “shared sovereignty.” These are not strategies. They are moods.

Middle powers do not constrain superpowers by holding hands. History offers no counterexample. Superpowers bargain seriously only with other superpowers. Everyone else is managed, ignored, or pressured individually.

The speech flatters its audience by allowing them to feel relevant without confronting power. That is its genius—and its dishonesty.

II. Contradictions as Policy

Carney oscillates throughout the speech between calls for “strategic autonomy” and warnings against a “world of fortresses,” only to pivot moments later into earnest appeals for collaboration and shared values. The result is not nuance but incoherence. He wants independence without insulation, sovereignty without friction, and diversification without acknowledging dependency.

The effect is intellectual whiplash—followed by the familiar hunger that sets in after a meal of clichés. The language soothes, but it does not nourish.

Carney performs a neat rhetorical trick. He scolds idealists for wishing the world were different, then speaks as if wishing were policy. Dependency, we are told, is dangerous—but diversification is offered without costs, enemies, or arithmetic.

Sovereignty is praised, then instantly diluted into something that can be “shared,” as though power were a communal herb garden rather than a finite asset. This is not realism. It is reassurance dressed up as sobriety.

These are not nuanced positions. They are contradictions politely phrased.

Strategic autonomy means choosing. It means naming enemies, confronting domestic veto players, offending vested interests, and prioritising productivity, energy, and defence over symbolic virtue. Carney gestures at autonomy while refusing to name the forces—many within his own political coalition—that make it impossible.

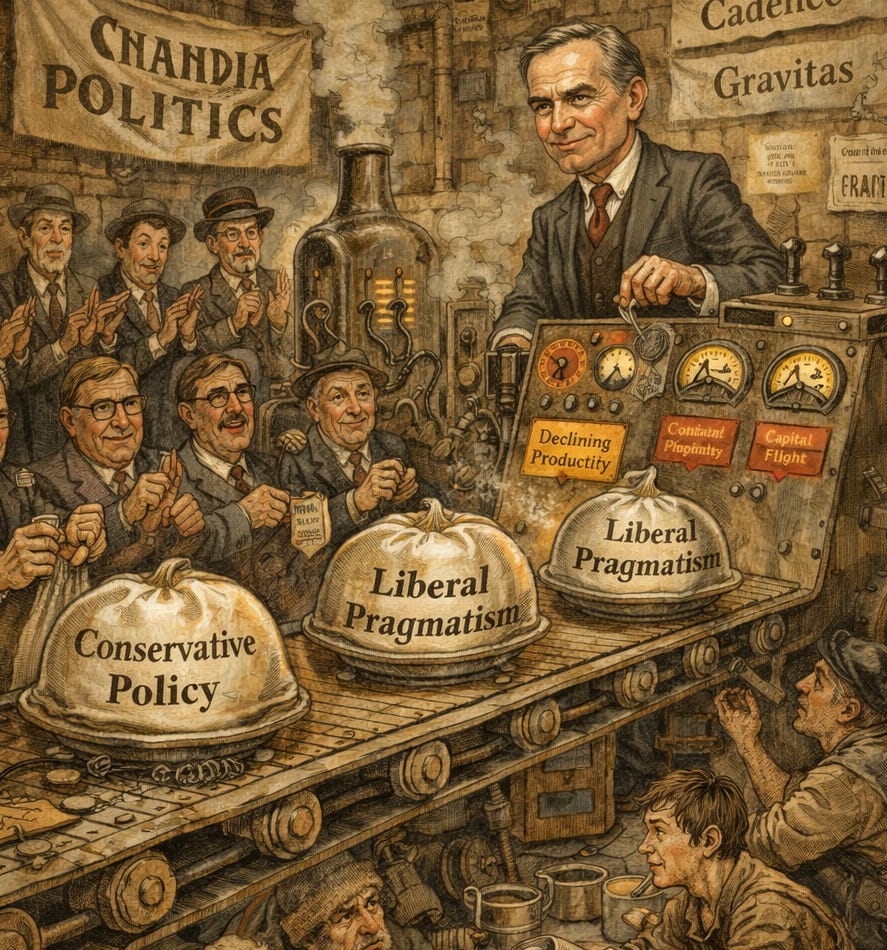

The most revealing aspect of the speech is what it quietly concedes. Carney now endorses:

Energy expansion

Military rearmament

Supply-chain security

Industrial policy

Interprovincial trade reform

These are not novel ideas. They are largely long-standing Conservative positions—denounced, delayed, or openly ridiculed by the Liberal Party for a decade.

Consider the handful of “serious” policy pillars now being paraded as evidence of Carney’s gravitas: energy expansion, military rearmament, supply-chain security, industrial policy, and interprovincial trade reform.

Energy expansion invites the simplest test of seriousness: does Carney possess the nerve to confront premiers, activist courts, and indigenous hereditary leadership structures—many lavishly compensated—when they veto pipelines, terminals, and projects of national interest?

His own record suggests otherwise. In Value(s), Carney treats hydrocarbons less as a strategic asset than as a moral problem to be laundered through jargon—most notably his enthusiasm for “net-zero” or “zero-carbon” oil, achieved via vast carbon-capture and storage schemes.

Vaclav Smil, one of the world’s leading energy scholars, has repeatedly described large-scale carbon capture (CCS) as economically marginal and physically incapable of delivering meaningful decarbonization, noting that it addresses symptoms rather than the scale of fossil-fuel use itself. One can find no better example of useless, symbolic, self-destructive false virtue than CCS.

Mark Jacobson of Stanford has been even blunter, calling CCS “a distraction that delays real solutions,” arguing that it is prohibitively expensive, energy-intensive, and has never worked at scale without massive public subsidy.

This is not a plan; it is consultancy cosplay—ideas designed to impress rooms, not to work in the world. The consultant is always gone before the wreckage appears, leaving others to clean up the mess while he congratulates himself on his foresight.

Military rearmament is no awakening either; it is the result of reality forcing compliance—specifically, an American president, however coarse, saying aloud what Washington long believed: Canada has been freeloading.

Supply-chain “security,” meanwhile, is left conspicuously vague, perhaps because spelling it out would expose either banal truisms or outright economic nonsense—the fantasy that nations can painlessly replace global production networks with domestic substitutes without cost, inefficiency, or inflation.

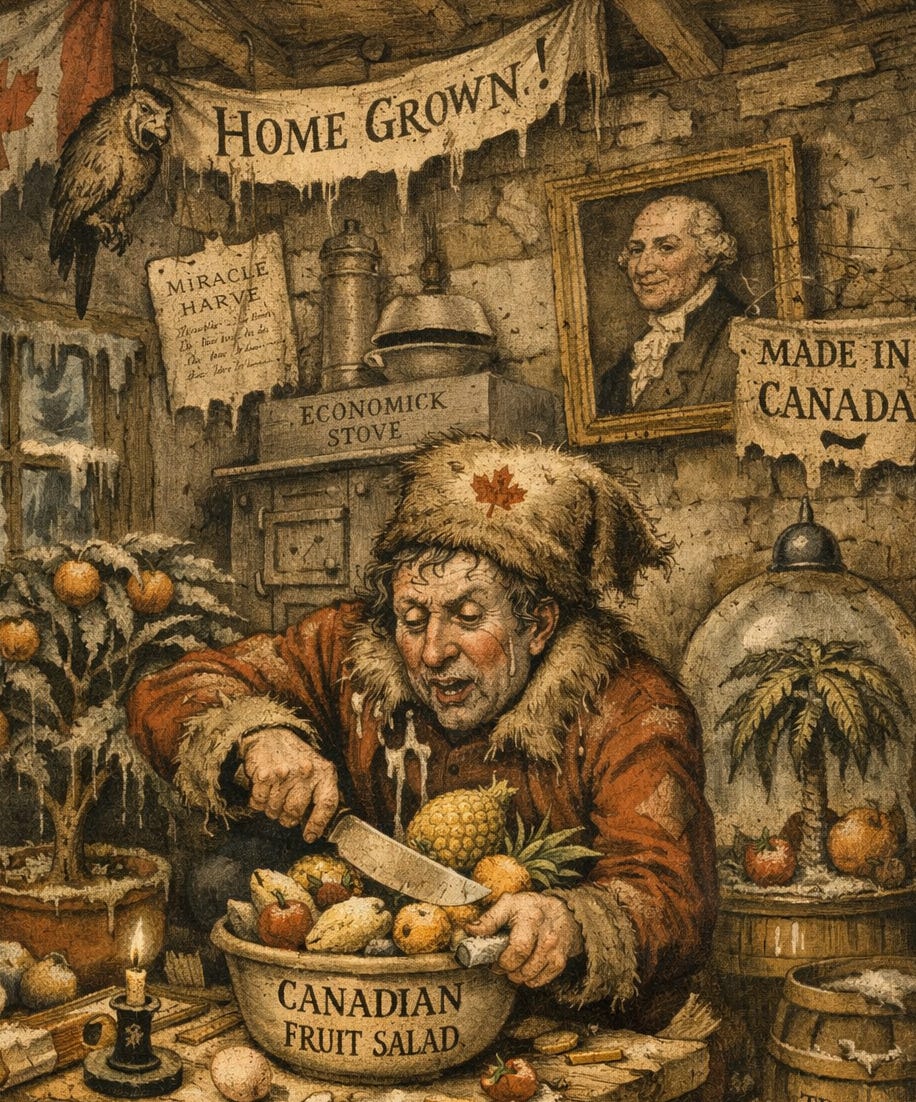

Economists have been warning against this confusion for over two centuries. David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage—the foundation of modern trade—explains precisely why “secure” self-sufficiency is impoverishing: countries grow richer by specialising in what they do relatively well, not by attempting to grow oranges in winter so they can boast of a proudly Canadian fruit salad. Paul Krugman2 has mocked this instinct repeatedly, noting that supply chains are not fragile ornaments but efficiency machines, and that forcing production “at home” merely raises prices while lowering quality.

To call this “security” is a category error; it is protectionism with a marketing degree. Industrial policy follows the same hubristic logic: the belief that governments can out-innovate markets by directing capital into fashionable sectors. Remember Carney and his Canadian-made car rants?

We have already seen how this ends. Industrial policy does not merely fail; it actively damages the economy by misallocating capital, perverting incentives, and rewarding political access over productive risk-taking. Businesses are pushed away from innovation and toward rent-seeking—learning how to lobby, comply, posture, and curry favour before they ever build anything of value.

The result is a familiar graveyard: battery plants that exist on press releases, green-tech subsidies that socialise losses while privatising gains, and corporate welfare regimes in which taxpayers absorb the downside and politically connected firms take the upside.

As for interprovincial trade reform, it is the clearest test of courage—and the one Carney is least likely to pass. Removing internal barriers requires confronting the very rent-seeking interests industrial policy creates: unions, supply-managed cartels, professional guilds, and provincial gatekeepers who thrive on fragmentation. Politicians have promised this reform for twenty years. None has delivered, because doing so requires standing up to one’s own coalition rather than flattering it.

Removing internal barriers requires confronting the very vested interests that fund and staff the Liberal ecosystem: unions, supply-managed cartels, professional guilds, and provincial gatekeepers who thrive on fragmentation.

On this evidence, Carney offers not a break from the past, but a carefully laundered version of it: Conservative ideas without Conservative resolve, ambition without confrontation, and rhetoric that avoids results that would be inconvenient.

Many sitting Liberal MPs still oppose the ideas Carney has borrowed from the Conservatives. Mark Carney himself opposed them in print, most explicitly in his book Values, where energy development is framed as a moral failure rather than a strategic necessity.

And let us not forget: Carney was not an external critic of the Trudeau government. He was its chief economic adviser, embedded in—and complicit with—the very policy framework that produced capital flight, collapsing productivity, and an energy sector treated as a moral embarrassment rather than a strategic asset.

And yet, in this speech, the same ideas reappear—unaccompanied by any admission of error. There is no “we were wrong.” No reckoning with the consequences of Liberal policy. There is only quiet appropriation, presented as evolution rather than reversal.

If Carney has had a road-to-Damascus moment, he has neglected to tell us about it. And when a politician adopts positions he once condemned without acknowledging the change, one should not assume growth. One should assume convenience. He is not acting out of conviction; he is simply curating his words to create an appealing message.

Such ‘values’ that dissolve the moment power is at stake were never values at all—only instruments for retaining it.

This is not leadership. It is rebranding.

The invocation of Václav Havel is not merely revealing; it is offensive.

Havel wrote about totalitarian systems sustained by compulsory lies, enforced by fear, punishment, and the constant threat of ruin.

To analogise Canada’s voluntary participation in Western alliances and democratic trade-offs to a Czech greengrocer coerced into hanging communist slogans is not just intellectually lazy—it is grotesque.

It trivialises the lived reality of Soviet repression and cheapens the moral weight of Havel’s work by bending it into a prop for a comfortable Western politician who risks nothing.

Which lies, exactly, are Canadians living within? Do alliances require compromise? Does that power matter?

If Carney believes we should “take the sign out of the window,” he owes us the courtesy of saying which sign, in whose window, and to what consequence. Instead, we get moral vapour.

III. The Human Cost of Symbolic Politics

The most grotesque omission in the speech is economic reality.

Canada’s per-capita GDP is declining. Productivity is stagnant. Capital is fleeing. Real wages are under pressure. Youth unemployment—particularly among those aged 18 to 24—is alarmingly high. These are not abstractions. They manifest as longer food-bank lines, rising addiction, broken relationships, deteriorating mental health, and suicide. People need work not only to eat, but to have purpose.

Layered atop this is a debt burden that is quietly spiralling out of control. When federal and provincial debt are combined—before even accounting for staggering household indebtedness—Canada’s fiscal position is deeply compromised. In the G7, we may not be the worst, but we are the tallest midget: marginally less reckless than some, catastrophically exposed nonetheless. This is not resilience. It is complacency masquerading as stability.

Against this backdrop, Carney boasts of having “cut taxes.” The reality is that the lowest marginal rate has been reduced from 15% to 14%—an amount that works out to roughly $1.14 a day for the average worker.

Corporate taxes? Nothing, so we can expect no Irish miracle here.

A minute tax cut has been greeted by commentators as bold relief for struggling Canadians. It is nothing of the sort. It is pocket change repackaged as policy, arithmetic concealed by applause. For those who do not run the numbers, it feels meaningful. For those who do, it is an insult dressed up as compassion.

In Toronto and Vancouver especially, home ownership—once a foundational rite of passage into adulthood—has been rendered mathematically unreachable for all but the children of the already wealthy, or the vanishingly small minority who step directly into six-figure salaries.

What should have been a broad social pillar has become a mechanism for class reproduction. This system of entrenched housing privilege flourished during the Trudeau era and represents a quiet but brutal form of intergenerational abuse, imposed by boomers on Millennials and Gen Z.

It is therefore no exaggeration to describe the boomer generation—at least in its politically decisive form—as Canada’s most selfish generation. They are the primary electoral base for Mark Carney.

Elbow uppers (he’s 20 points up on Poilievre with the boomers) do not see in him a figure of reform or courage, but a custodian of the status quo: a man who will preserve inflated asset values, protect indexed pensions, and ensure that the costs of economic stagnation are borne by those with the least power to resist them.

For this cohort, decline is tolerable so long as it is gradual, abstract, and borne by someone else.

Yet for a large and politically decisive cohort—asset-rich, mortgage-free boomers cushioned by indexed pensions and Old Age Security—economic decline barely registers as danger. It is experienced as a mild inconvenience. For them, “standing up to Trump” is a harmless emotional indulgence, a dopamine hit of national self-regard that costs them nothing they can feel.

This is the same Marie-Antoinette arrogance we heard when Chrystia Freeland breezily reassured Canadians that tightening their belts wasn’t so bad—after all, she had cancelled Disney+. The assumption is grotesque: that economic pain simply means ordering a $4 Americano instead of a $6 cappuccino.

Try delivering that sermon to a parent whose child asks why they’re still wearing last year’s clothes, or why meat that actually tastes good has disappeared from the table. That is what this politics amounts to: affluent moralists congratulating themselves on symbolic defiance while the costs are quietly downloaded onto people with no buffer, no assets, and no applause.

For everyone else, it is cruel.

I have a friend, 34 years old, single, living an almost aggressively modest life. She earns $84,000 a year. Her apartment is small, tasteful, furnished with IKEA restraint rather than indulgence. And yet well over half her net income disappears into rent. By the end of each month, there is almost nothing left—nothing to save, nothing to build with, barely enough to help support a mother in Toronto who herself is barely getting by.

This is what “affordability” looks like beneath the slogans.

Poking a finger in the eye of the president of the country that absorbs roughly 75 percent of our exports is not bravery. It is recklessness. It is easy to applaud symbolic defiance when you are insulated from its consequences. The boomers love the emotional rush of standing up to Trump.

It is small business owners, young workers, and families on the margin who pay the price for the retaliation from the eye poke.

I have a neighbour who owns a small business. Since the tariffs went into effect, his income has decreased by roughly 30 percent. He is laying people off. This is what “elbows up” looks like in the real world—not a slogan, not a posture, but paycheques vanishing and livelihoods quietly collapsing.

As for me, I saw my own income reduced by nearly 90 percent overnight. Not by market forces, but by institutional savagery: I was fired because I dared to call a terrorist organisation with documented Nazi ties exactly what they are—Nazis. The Palestinian mob took me down.

Economic loss is easy to dismiss from a distance. It becomes something else entirely when it moves into your living room, sits at your kitchen table, and begins quietly rearranging your life.

Carney speaks of diversification as if Canada had a policy of refusing to trade outside the United States. We do not. Nor can we realistically replace the American market for energy, minerals, forestry, and agriculture—sectors constrained by geography, infrastructure, and logistics.

Saying “we should diversify” is not a plan. Nor a new idea; it is driven by the business sector, not the feds. As Carney uses it, it is a platitude.

Carney himself is the elite of the elite. He has never worried about rent, groceries, or keeping the lights on. He travels in limousines that idle at the curb. Has the man ever pumped his own gas? Expecting him to grasp the lived reality of economic decline requires an act of faith unsupported by evidence.

If one is serious about lifting the poor rather than managing them, the conclusion is unavoidable: Conservatives can—and should—be the party of the poor precisely because they are the party of productivity.

Poverty is not defeated by shuffling existing wealth; it is defeated by creating more of it. Rising productivity raises wages, expands opportunity, lowers prices, and turns the poor into the self-sufficient rather than permanent clients of the state. That is how societies actually move people up the ladder, not sideways across it.

The Liberals have become the party of the credentialed, asset-rich elite who mistake redistribution for virtue.

The NDP is the party of grievance economics, animated by the fantasy that wealth can be endlessly divided without ever being produced.

Only a politics that prioritises productivity growth—capital investment, energy, trade, and work—can generate real, durable prosperity. That is not cruelty; it is arithmetic. And it is the only anti-poverty program that has ever worked at scale.

Conclusion: Style Is Not Substance

This is why the speech was praised. It flatters the listener. It reassures without demanding. It allows one to feel informed without learning anything. It commits Carney to nothing measurable, nothing falsifiable, nothing that risks offending the interests that sustain his coalition.

That is not a failure of execution. It is the point.

Calling this a “great speech” is not a compliment to Carney. It is an indictment of a media class and political culture that confuses eloquence with thought, vibes with vision, and branding with courage.

Canada does not suffer from a shortage of speeches. It suffers from a shortage of truth.

And until we learn to tell the difference, we will keep applauding while the till is emptied—congratulating ourselves on our moral posture as the country grows poorer, duller, and less serious by the year.

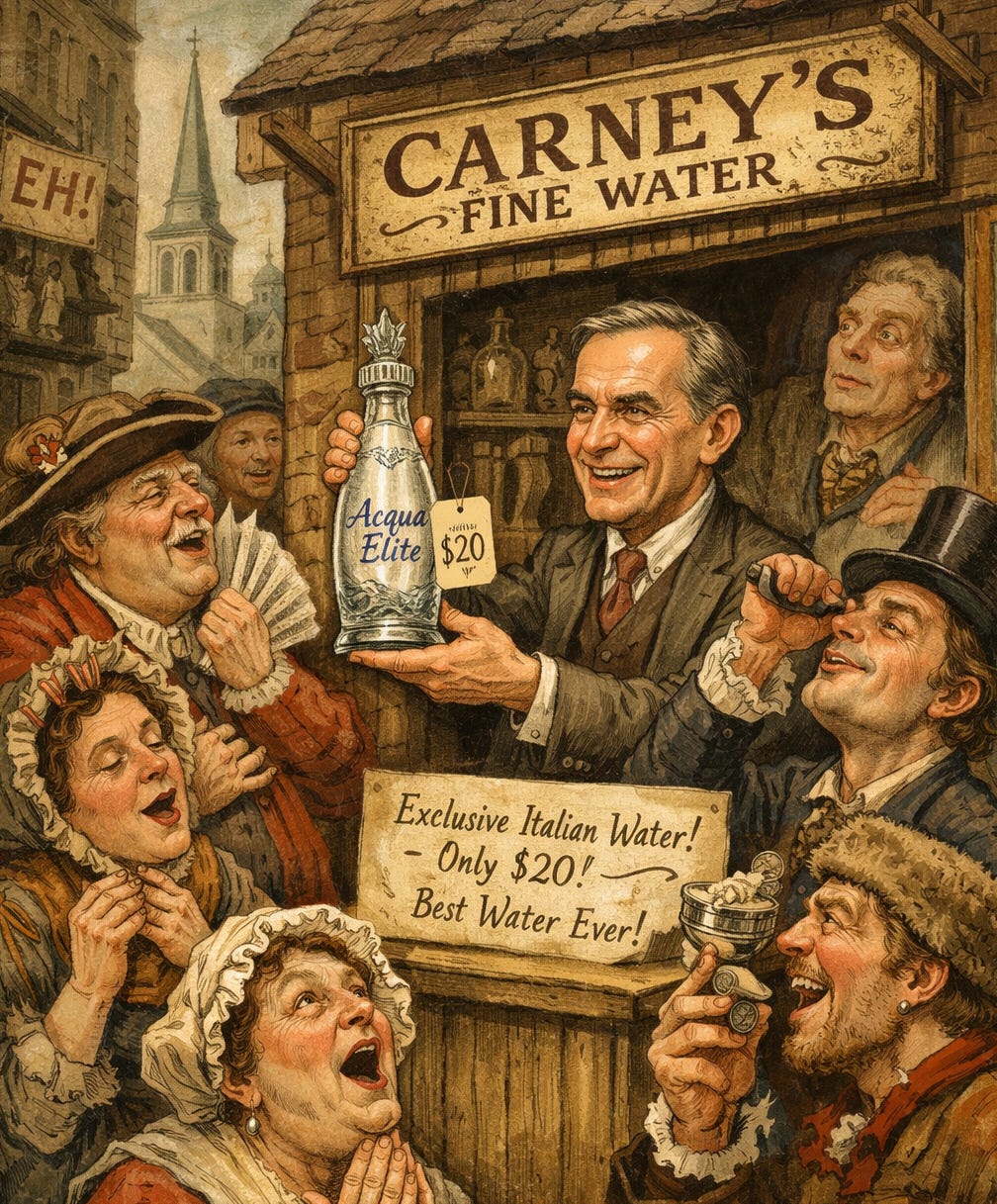

In truth, nothing fundamental has changed. Carney has not discovered a new spring. He has not purified the water. He has simply taken the same old tap water—policies recycled, contradictions intact, failures politely forgotten—poured it into an elegant, absurdly expensive bottle, screwed the cap back on, and placed it on display in his little shop of abstractions.

Canadians wander past, swoon at the glass, admire the label, and buy it eagerly. Then they stroll the streets announcing, with self-satisfied wonder, that this is the finest water they have ever tasted.

The problem is not the bottle.

The problem is not even the salesman.

The problem is a country that no longer remembers what clean water actually tastes like—and applauds as it drinks whatever is handed to it, so long as the packaging flatters its pride.

Writing in the 5th century BCE, Thucydides chronicled the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, not to celebrate heroism, but to explain how power actually works. His central insight is stark: states act according to their interests and power, not virtue, and weaker states survive only by recognising this fact early enough to adapt.

The most famous passage, the Melian Dialogue, strips politics of illusion. Athens tells the neutral island of Melos that justice applies only between equals in power; “the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.” Melos appeals to morality, international norms, and hoped-for allies. Athens responds with reality. Melos is destroyed.

For Thucydides, this was not cruelty—it was inevitability. Words do not restrain power; force does. Alliances matter not because they are virtuous, but because they change the balance of power. Small states that imagine they can float above great-power rivalry by invoking principles invite catastrophe.

Thucydides’ lesson is not cynicism, but clarity: survival requires carefully choosing alliances, accepting constraints, and never confusing rhetoric with leverage. Moral language without power, he shows, is not nobility—it is self-deception.

The economic case against “supply-chain security” as a form of national self-sufficiency is not controversial. It originates with David Ricardo, who demonstrated that nations grow wealthier by specialising according to comparative advantage, not by attempting autarky or duplicating production inefficiently across borders (On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, 1817). Modern economists have repeatedly reinforced this point. Paul Krugman has argued that global supply chains are efficiency-enhancing networks, not fragile dependencies, and that forcing domestic substitution in the name of “security” raises prices, lowers productivity, and ultimately reduces national welfare (see Krugman, Pop Internationalism, 1996; and “Ricardo’s Difficult Idea,” Fortune, 1998). In this framework, “secure” supply chains achieved through protectionism amount to growing oranges in winter—possible, but ruinously expensive.

Well analyzed and outlined.. Carney has and will stoop to any level of commentary without regard to reality because the chances of his liberal government having to generate results are zero.

And then there is always a grocery credit to announce that lowers food expenses for 10% of the population in a year or so.

I didn't listen to his speech because I know he is a smooth talker. He should be, he has had lots of practice in the upper echelons of society.

I read the transcript - reading allows you to digest what was said without having to endure how it was said. A lot of people have said they listened to it, but did they listen all the way through, or just the selected sound bites show on the nightly news. Or worse, repeat what the talking heads on the nightly news said.

Love the comment about how people suddenly become more interested in their phones or suddenly remember they need to do something else when you start asking about the substance of the speech, or any speech.