The Small Republic of Particulars

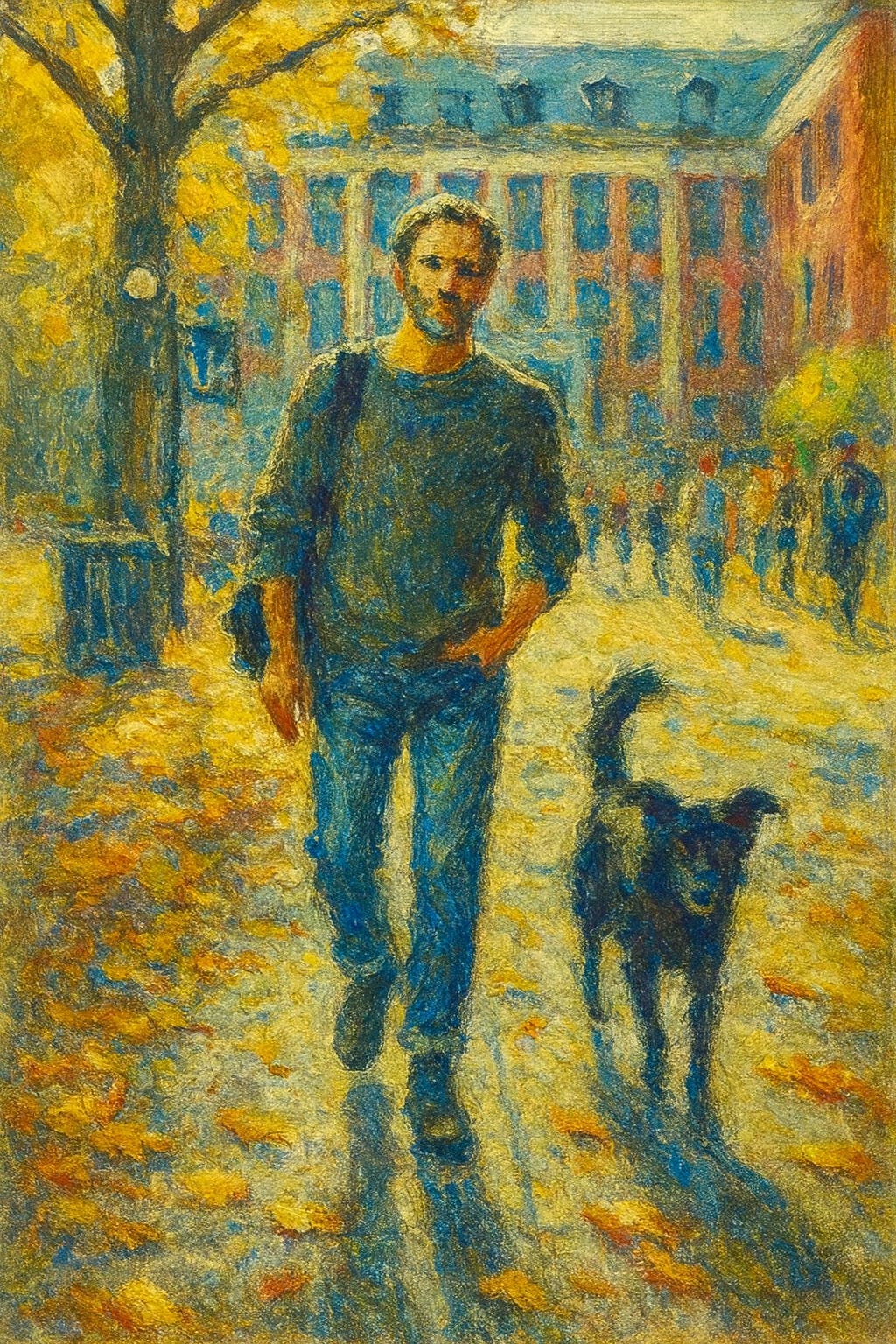

On sunlight greetings, the discipline of gratitude, and walking the black dog without letting him lead.

If you believe in the importance of free speech, subscribe to support uncensored, fearless writing—the more people who pay, the more time I can devote to this.

Please subscribe to receive at least three pieces /essays per week with open comments. It’s $6 per month, less than USD 4. And now take 50% off.

Everyone says, "Hey, it’s just a cup of coffee," but please choose my coffee when you come to the Substack counter. Cheers.

(Rewritten in August, 2025)

I stepped out with the dogs and was greeted by a Toronto mid-October sun doing its best imitation of late June. A surge of happiness went through me. Perhaps the photons persuaded a few neurons to stop sulking and pass notes like civilised cells; perhaps it was just one of those meteorological flukes—weather on the skin, weather in the skull. Had I earned it? Or had it arrived, like most blessings, without receipts or tracking numbers?

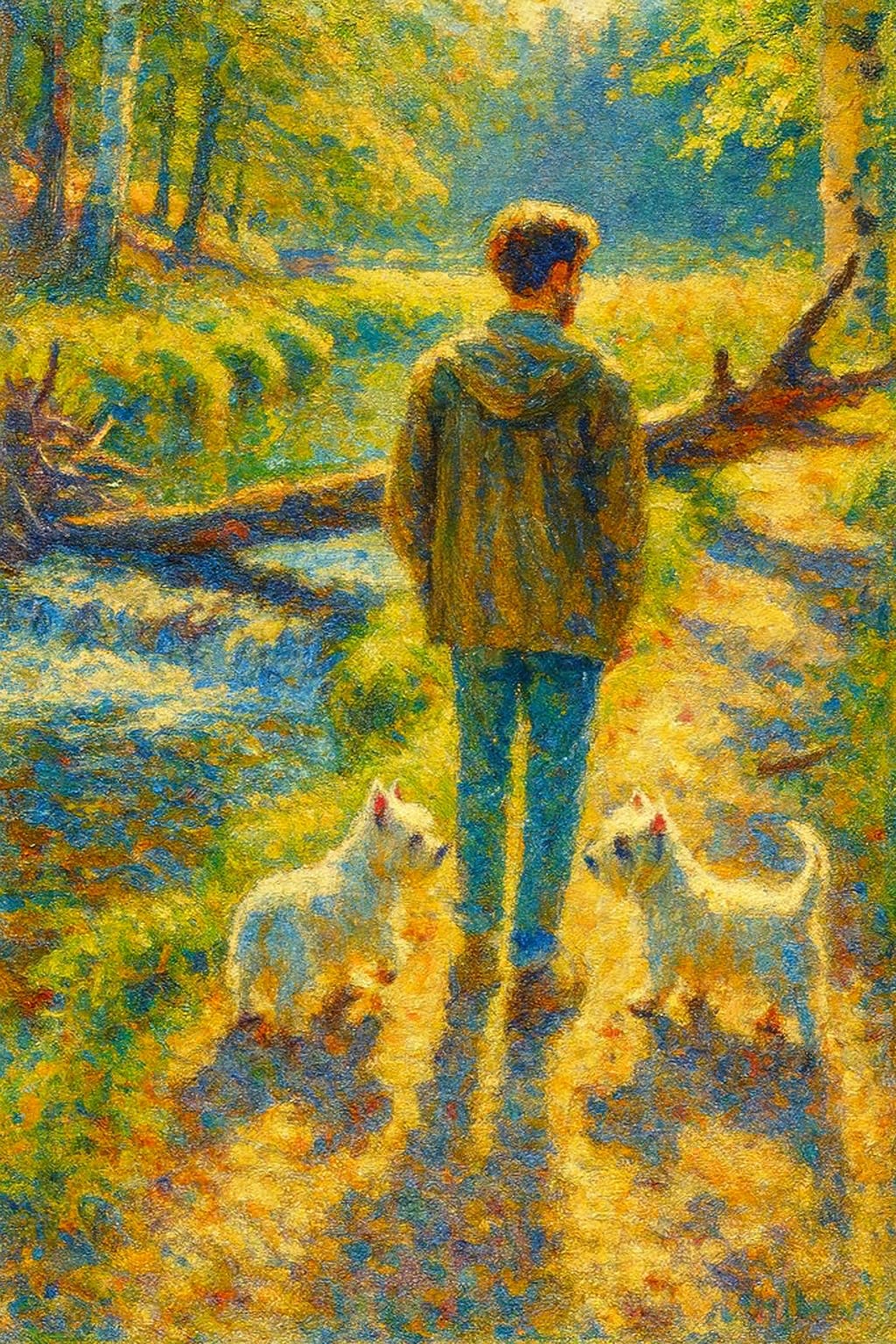

It lifted my step but only for a street’s worth. Do other people live like this permanently—sunny-side up as a lifestyle choice? Was the lift the product of anything I’d thought, or merely the nervous system tossing me a biscuit? My terriers’ joy—two white rockets launched from the porch—seemed the likelier primer. Gratitude for their enthusiasm, then euphoria at the end of the drive: cause and effect, or just a coincidence dressed up as meaning?

It sounds indecently analytic, but depression teaches you the housekeeping of the mind. You learn what’s in the cupboard and how easily it goes stale. Some months I could keep a grip on gratitude; other months it was like holding a greased doorknob. The CV said the right things—education, marriage, children, career—those conversational credentials one flashes at new acquaintances to prove one has joined the ride. Yet I suspected I’d spent more time than most in Thoreau’s waiting room.

“The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called resignation is confirmed desperation” (Walden, 1854).

The line is quoted so often it’s become hotel-lobby décor—pleasant, familiar, and largely ignored. Yet clichés earn their status by telling the truth to so many people at once that the words wear thin and look cheap. Meaning stretches, nuance evaporates, and what once fit like a tailored coat now hangs like a sack, leaving its users sounding equal parts lazy and dim.

I never felt I wore a mask; the melancholy was all too eager to introduce itself. It behaved like one of those immovable guests who ignore the yawns, the dish-stacking, the clinking vacuum attachment—and stay still parked on your sofa, chipping away at your composure.

I tried to bribe it. I trafficked in outlook futures: promises of reform, new regimes, all the usual January merchandise. Half-hearted, of course. I was both salesman and mark; the patter fooled no one. Change, viewed at a distance, is a cathedral. Draw near and you discover it’s a charming model in a gift shop snow globe.

Still, that small sunny ambush at the curb felt like a subpoena. Use it. Put the moment on the stand and ask the better questions.

Is gratitude an emotion or a discipline, a frisson1 or a frame? Is it chemistry—serotonin scrubbing up for duty—or the mind selecting, at long last, the right lens? I’d always dismissed “chasing feelings” as a fool’s errand: you sprint, they dawdle. But perhaps I’d been too doctrinaire. Perhaps you can’t command feelings, but you can conscript perspective.

There’s some modest science to back a man’s hunch. The sunlight alone is not just theatrical lighting: even the dullest public-health pamphlet now concedes bright light nudges the serotonin shop floor into action and, come evening, lets melatonin clock come in on time.

Clinical trials—the unromantic cousins of experience—suggest gratitude exercises move the needle for mood in the same small, stubborn way that flossing moves the needle for teeth. Not miracle cures, just proof that daily tedium can be medicinal. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) calls it “reframing.” The Old Testament calls it thanksgiving. Either way, it’s the same craft: learn where to fasten the frame so the picture can be seen.

Discipline implies possibility. If we are the sum of our habits, then a change of habits is a change of that sum. Sixty years old arrived the other day and, like a tax auditor with impeccable manners, asked to see my records. I hadn’t expected a number to be so gregarious. Fifty-nine scarcely wrote; sixty sends frequent emails. Many of my best friends from boyhood now appear mostly in anecdotes. Two didn’t make it to 53.

When the ledger shows losses, gratitude seems like creative accounting. But perhaps that’s when the books most need balancing.

I tried a thought experiment: introduce the thirty-year-old to the present owner of the body. Would the younger one be impressed? No. Relief is closer to it—a quiet, business-class contentment. Contentment is a sturdier fare than gratitude: meat and proper potatoes, not the tray of petits fours you admire and pretend you didn’t eat. Contentment folds ambition neatly and files it lower in the drawer—not banished, merely demoted from tyrant to clerk.

My father managed this without attending a single mindfulness seminar in a repurposed yoga barn. He never led with a job title when meeting strangers; I’m not sure he always remembered his job title.

Luxury goods were to him what Latin tags are to a hockey commentator—an amusing affectation for other men. He didn’t renounce anything. He simply never wanted it. His equanimity made a persuasive case: without contentment, gratitude is a speech; with it, gratitude is a view.

Keats knew the vantage point. Read “To Autumn” aloud and hear how reverence turns landscape into liturgy:

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

I remember the lambs on my Irish cousins’ hill, jaws working side to side with that solemn herbivore concentration, companions folded neatly on the grass, hooves tucked under like careful punctuation. Chekhov would have noticed the particulars: the click of a gate not quite shut; a thread of wool snagged on wire; a kettle beginning to think about boiling.

The modern manuals—CBT handbooks and Sunday sermons—converge here. Make the list. Give thanks in all circumstances. One must be careful, of course: if you go chasing gratitude merely to evict the melancholy, the transaction can cheapen both—like marrying for money and discovering the money resents you. But perhaps motives can be mixed, as recipes often are, and still produce something edible.

I’m writing to myself here, I dislike unsolicited advice, and don’t want to be a faucet someone forgot to close.

Acknowledge goodness first—the ballast under the deck. Acknowledgement doesn’t emote; it undergirds. In older economies of faith, gratitude was communal—a psalm sung in plural.

Now we outsource connections to rectangles that blink, and a living room becomes a museum of doors. Everyone has a private screen; only the dogs still sprint downstairs like hounds in a 19th-century print, claws skittering on hardwood, collars clacking, joy conducting its little orchestra.

Even the dogs refuse solitude.

Discipline says: do the thing. Gratitude lists in trials—the dull kind with consent forms—show measurable upticks in resilience. But the trick is not waiting for feelings to arrive with a flourish; it is laying out a chair for them anyway. You can’t “not think” your way out of gloom; you must think toward something. Fill the room with particulars, and the shadows negotiate.

Experts give it a name so unromantic it must be reliable: cognitive reframing. A frame demands attention; it says: stop, look. The wall won’t hang the painting for you. You must lift it, find the stud, and commit.

So I curate. The other night in the park, the terriers wore glow collars—one red, one green—like off-brand lighthouses. I threw a scuffed yellow tennis ball down the slope where the grass has given up in patches, and they barreled after it as if the ball were new. The sound—four paws per dog, eight-beat percussion—was its comic metronome. They returned panting, pleased to be in on the joke.

Two evenings later, we queued for a Halloween fright night on three unprepossessing acres at the city’s sleeve. The line stalled in that democratic way; nobody wanted to spend the extra $10 on the fast line.

Teenagers, expertly painted into monsters, flirted with shrieks that were audition pieces for joy, not fear—the air smelt of sugar and damp plywood.

Dry ice ambled around our shoes like low cloud, and my daughter took my arm—the instinct as old as daughters and fathers. My mother-in-law had retreated to the car with dignity and relief. Inside the maze, we were briefly a unit of four again. A tiff evaporated somewhere between the ghoul with the plastic axe and the corridor of rubber hands.

When the last scare resigned and we emerged onto a dirt lane and a parking lot, my son asked for the keys. He drove with the concentrated solemnity only a new car can extract. At our street, I recognised my daughter’s brake lights; she’d beaten us by one intersection. At the house, the dogs shouted their gospel of return and bolted to the porch, as if we’d been gone to sea.

The literature says gratitude fosters resilience—there are charts, small upticks, sober effect sizes. None of it erases. It merely tells you where to aim the eye. My instinct is to look down, an archaeologist of grief. But instincts are only habits with a head start.

The geese at the dog park convene at dusk, conducting their old business in that throaty ka-lonk—municipal but dignified. I can list twenty irritants before breakfast: a rock through a synagogue window, a van’s head gasket sulking, fingers that go numb and stage a strike. The ledger threatens red ink.

And then—because the discipline requires it—I list back: the strong tea at 4 p.m.; the maple bark rough under a dog’s imploring paw; a neighbour’s wave mis-timed but sincere; my wife’s laugh arriving one second before the joke; a son’s careful left turn; a daughter’s arm around mine in fake fog.

Contentment is narrow and reliable, like a farm path between tall grass. Leave it, and you discover the margin is pocked with holes. I try to keep to the firm track, even when the scenery argues for detours.

When the rain quits, I’ll walk the dogs. Two white triangles of ear will lift at the word, the way semaphore flags snap in a salt wind. They’ll spin in competent circles, thrilled by the administrative procedures of leashes and zips. We’ll set off toward the strip of woods where the path dips, and rabbits bolt in their indecisive spurts while squirrels elastically ascend a maple, the brown paws working the bark as if typing.

The brook will narrow and chatter where a fallen trunk breaks the flow.

We’ll continue because leashes are short. The dogs will come to terms with their thwarted pursuit. On we’ll go, past sumac pretending to be torches and the sky bringing an early dusk.

There is enough good to turn toward, if only one turns. The lists help. They put a spine in the day. They stand, as furniture once did, on four stout, unfancy legs.

And if the black dog shadows us down the path, let him. We’ll keep walking. The collars will blink, the brook will work around the obstacle, and the geese will conduct their minutes. For now, in this small republic of particulars, all is, if not perfect, in order.

If you found value in this article and wish to support my ongoing work, please consider leaving a tip. Your support helps me continue producing uncensored content on critical issues.

A frisson is a sudden, brief, and intense feeling of excitement, pleasure, or emotional thrill—often accompanied by a physical sensation like chills, goosebumps, or a shiver down the spine.

No fun when the black dog visits. There is a lot to be depressed about these days, especially if you spend much time on devices or following news broadcasts. Gratitude may not lift the cloud, but it reminds me that the cloud will eventually pass and the sun return. My mom always said to turn on all the lights indoors on gloomy days. Having weather dependent moods, I follow that advice. I have only needed medication one time, 24 years ago, but it helped. What I choose to read matters. My ‘blue blanket’ since October 7th has been Regency romances, of all things! In the middle of the night, I turn to books about trees or to poetry. The escape from bleakness may be temporary, but even temporary respite is healing. Exercise is great. Dogs are great. Family can be a comfort. Wishing you occasional joy into the mix.

Thank you