Addendum to The Loss of a Simple Cat

An Ode to Sweet Masha and an Examination of the Effect of New Life on Old Griefs

I wonder, is there a tall wall between pet lovers and those who are not? Do the non-pet lovers look at us as if we are quite mad, grown adults undone by the loss of a creature that cannot speak? Perhaps.

Nevertheless, I would say to them, quite gently: don’t read this piece. It isn’t for you. And that’s fine. My next piece will surely solve all the world's problems and will not mention cats.

I am not ashamed of my love for a small creature, nor to find myself weeping, driving home on a Sunday evening, glancing over at the passenger seat and seeing an empty pet carrier, as if the life of my lost cat were a poem and the carrier was a period, a full stop.

I parked the car, and with the bag over my shoulder, stepped into our house - my beloved daughter — nineteen, fragile, incandescent with grief — flew toward me, sobbing.

There are moments when one feels that the air itself recoils from human pain, and this was one of them. These are the moments that mark life, the ones the aged recall in the senior’s home.

It was also Sophia who had flown with me to Vulcan, Alberta, on the first anniversary of my father’s death, to stand beside me once more in that impossible mixture of duty and remembrance.

In the cemetery, the snow lay deep, soft, and unbroken — except for one small defiance: the marker of my father’s grave, the only one uncovered, covered by flowers that would not last, a dark rectangle amid a white sea, as if the earth itself had kept vigil while everything else slept.

Boris Pasternak wrote in 1912:

“The snow’s burning light, like a funeral,

Brings peace to the nerves, the body—

But a peace that comes from exhaustion,

Not from mercy.”

Yes, it was a peace from exhaustion. It seemed less like a graveyard than a field of exiled thoughts — each mound a quiet refusal to speak. The austerity of the snow broken by the flat marble marker with my father’s name stood against the wind, the lone survivor of the storm’s mercy.

And yes — before anyone feels moved to mention Simba’s Circle of Life — I’ll spare you that.

Life, as I have come to know it, is no circle. It is a crooked path through the snow, where we bury love and keep walking, one step at a time, carrying the ache like a lantern.

But do not tell me we do not carry the lantern. Only monsters do not carry lanterns.

As to the question of whether it is right to mourn a cat in a world so full of grief and loss?

The world echoes and shakes with the larger griefs: the stabbing in England, the war in Ukraine, the flood in Jamaica, the killings in Sudan.

By comparison, the death of a cat seems inconsiderately small.

But that, I think, is our defect as a species — the compulsion to compare. We weigh pain as if on a moral scale, each sorrow measured against a greater one, until no private grief is permitted dignity.

Follow that arithmetic far enough and we end up with one solitary sufferer — the universal Job — whose misery alone would count. Far better, surely, to hold the great and small griefs apart, each in its own space, neither denying the other.

And so we do. Then I might be permitted to mourn the world’s pain and the loss of Masha.

But now there is Vika — a blue-eyed ragdoll cat who, in theory, should adore dogs. In practice, she does not. She did not read her breed description.

For Vika eyes them with deep suspicion, while the dogs, bewildered by this small aristocrat, trail her like paparazzi. The peace is uneasy, the truce fragile, and I watch like an anxious diplomat trying to prevent another war.

Sometimes I wonder if her arrival came too soon — if welcoming Vika somehow betrayed Masha. Strangely, the new life makes us miss the old one more. The absence feels sharper against this bright, unsteady presence. Yet perhaps that is the point: love renewed, not replaced. Vika is so small and delicate.

I have come to think that pets are among God’s few unambiguous gifts — creatures lent to us for a season, to test our gentleness.

Yes to animals, we owe them kindness before men and before Heaven. We did that with Masha, and now we shall do it with Vika. Youth replaces age, but not love.

She is here now — beautiful, nervous, alive — and though her presence does not close the wound, it keeps the heart beating beside it. And that, perhaps, is all the healing one should expect.

_______________________________

The original entry was three weeks ago—see below.

Although the title of this Substack is Freedom to Offend, you know that when I write about my dearly departed cat, I am not a large organisation but one man behind a keyboard who loves his family, his children, and yes, his pets.

And if you are offended by a man lamenting yesterday’s loss of his cat, you surely have no heart.

I know that when people scroll through Facebook and see posts about the loss of a pet, many may skim past them, roll their eyes, and move on.

But our cat, our dog - they are family, they greet us at the door, they wait for us, and they measure their days by our presence. They ask for nothing but our company and give everything in return.

In our digital age, they are retro; they are always there.

Our beloved cat, Masha, who passed away last night after sixteen wonderful years, was one of those souls. She had no ambitions beyond love. She spent hours by my wife’s side as she studied or worked, content simply to be near her.

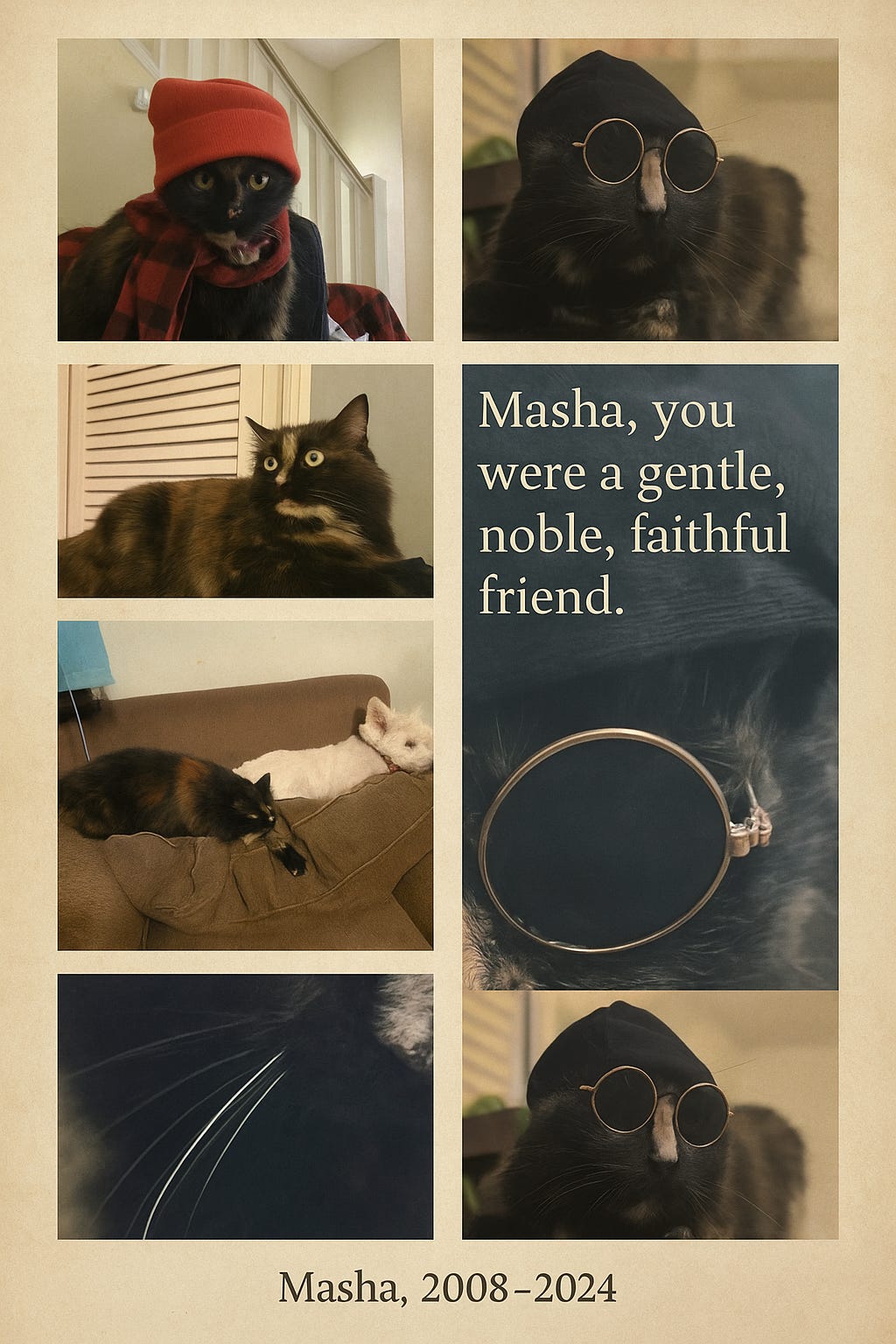

She chased our dogs when their play got too rough, sat patiently in front of the camera as my daughter and her friends put costumes on her, and grew calm in my lap as she rested in her final hours.

She would sit quietly, usurping the dog’s bed, but meow loudly when she wanted to go into Vanya’s, Baba’s room or the office. She did what she wanted; she was a cat, with a little feral blood flowing through her.

One day, she even followed the kids to school.

She found peace just being part of the rhythm of our home. That was her joy — to belong, to love, and to give warmth without ever asking for anything back.

To come home with an empty pet bag to your beloved 19-year-old daughter sobbing, running to you disconsolate—the parent’s pain is the child’s pain, oh how I wish I could take it away. My daughter remembered no life without Masha.

Of course, the loss of a pet is trivial compared to the heartache, grief, and sorrow that fill this world. But in our small, wonderful cloisters called families, these losses matter deeply.

Masha, you were a gentle, noble, faithful friend.

Let us not pretend this sorrow is some modern indulgence, a soppy byproduct of our softened age. No, the poets and sages of old knew it well—this piercing bond with our cats and dogs, these mute companions who weave themselves into the fabric of our days, only to unravel us when they depart.

Turn back the pages to antiquity, and you’ll find the Egyptians deifying cats as embodiments of Bastet, guardians of the hearth, their loss mourned with rituals that shamed the pharaohs’ own funerals.

Dogs, too, were etched into the epics: Homer’s Odyssey gives us Argos, the faithful hound who waits twenty years for Odysseus’s return, only to recognise his master and die in contentment—a scene that tugs at the soul without a trace of sentimentality, reminding us that loyalty outlives even the gods’ caprices.

By the medieval era, our forebears had woven pets into proverbs and verse, acknowledging their familial role with a wry nod to human folly. “A cat may look at a king,” they quipped, granting the feline an equality that mocked the hierarchies of men.

And dogs? “No more trust than in a dog’s tail,” a caution against fickle affections, yet underscoring how deeply we relied on their steadfastness in our households

Historical tomes reveal that dogs were domesticated some 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, evolving from wild predators to hearthside kin. Their presence shaped family life across cultures—from the Celts burying dogs with honours to the Romans inscribing epitaphs for their hounds as if for lost children.

Cats followed suit around 6,000 years later, slipping into homes as pest controllers but staying as silent confidants, their independence a mirror to our own vulnerabilities.

In the Enlightenment’s glow, poets like William Cowper captured this intimacy with unvarnished grief. In his “Epitaph on a Hare,” Cowper laments the death of his pet Tiney: “Though duly from my hand he took / His pittance every night, / He did it with a jealous look, / And, when he could, would bite.”

Here is no idealised fluff, but a witty acknowledgement of the creature’s prickly soul, yet the loss stings all the same, a testament to how these animals become extensions of our eccentric families.

Lord Byron, that rogue of romantics, poured out his heart for his Newfoundland dog Boatswain in 1808: “Near this spot are deposited the remains of one who possessed Beauty without Vanity, Strength without Insolence, Courage without Ferocity, and all the Virtues of Man without his Vices.”

Oh, the bitter wit in elevating the dog above humanity—yet the grief is raw, unashamed, as Byron declares the beast “more sincere than man.”

Matthew Arnold, in his elegy “Geist’s Grave” (1881), mourns his dachshund with a father’s tenderness: “Thou wert the lesson of the way / To live, to love, to die.” The poem unfolds the dog’s place in the family circle, a small life that amplified the household’s joys and now leaves it diminished.

And Mark Twain, ever the satirist, observed of cats: “Of all God’s creatures, there is only one that cannot be made slave of the lash. That one is the cat. If man could be crossed with the cat, it would improve man, but deteriorate the cat.”

But beneath the humour lies admiration for their autonomy, a quality that makes their voluntary companionship all the more precious—and their absence all the more hollow.

Yet for all this historical weight, the pain remains achingly personal.

Masha’s departure echoes these ancient laments, a reminder that in loving these creatures, we court a sorrow as old as domestication itself.

We grieve not despite their “triviality,” but because they reveal our capacity for pure, uncomplicated love—in a world that so often complicates it.

And in that grief, there is a defiant wit: For what greater offence to the cynics than to weep openly for a cat who asked nothing and gave all?

These little creatures slip so gently into our hearts, and when they leave, we feel an emptiness, a longing, a separation. We are not ashamed to grieve or cry for a cat.

Our Masha.

The house feels empty without you—quieter, slower, somehow less alive. You were not at the door when I came in this morning. I miss you so much, I cannot think of you today without tears. Goodbye, my sweet cat.

P.S. I was ranked #75 on humour; I had been #16. I think the fall may continue.

The dogs below are still trying to understand this new creature.

Malibu looks at Vika, inquisitive, curious, afraid.

So sorry to read about the loss of your beloved Masha! When our cat Gogh-Gogh died, my husband, who never wanted a cat - found them creepy - mourned for a week. On a walking path in Toronto, a family dedicated a pet fountain with plaque to honour their beloved pet. In part it stated”…Born a dog, died a gentleman.”

So sorry to hear this, Paul. You wrote so beautifully about Masha - your love for her really shines through. My deepest condolences.