The Forgotten Bloody Imperialist March of Muhammad.

It's impressive how a march that killed many more (and in half the time) than what the British Empire ever did in all its years is conveniently forgotten.

If you care about free speech, subscribe. It means I can continue doing this without needing to ask a gender-neutral AI for spare change. Please subscribe to get at least two uncensored, impolite, fire-in-the-belly essays per week. Open comments, $7/month. Less than \ USD 5. Everyone says, “That’s just a cup of coffee.”

Okay, then buy mine.

History, when it is permitted to speak without the narcotics of modern guilt or selective memory, does not whisper—it bellows. And what it tells us is that human civilisation has been built, shattered, and rebuilt atop pyramids of the dead. In that ledger of imperial expansion, the early Islamic conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries stand among the most explosive and deadly episodes ever recorded.

In barely a century—less time than it took Rome to secure a single province—Arab-Muslim armies expanded their dominion by more than 600 to 700 percent, swallowing territory from the Atlantic to Central Asia, and leaving an estimated 30 to 40 million dead through warfare, enslavement, famine triggered by upheaval, and the collapse of pre-Islamic societies.

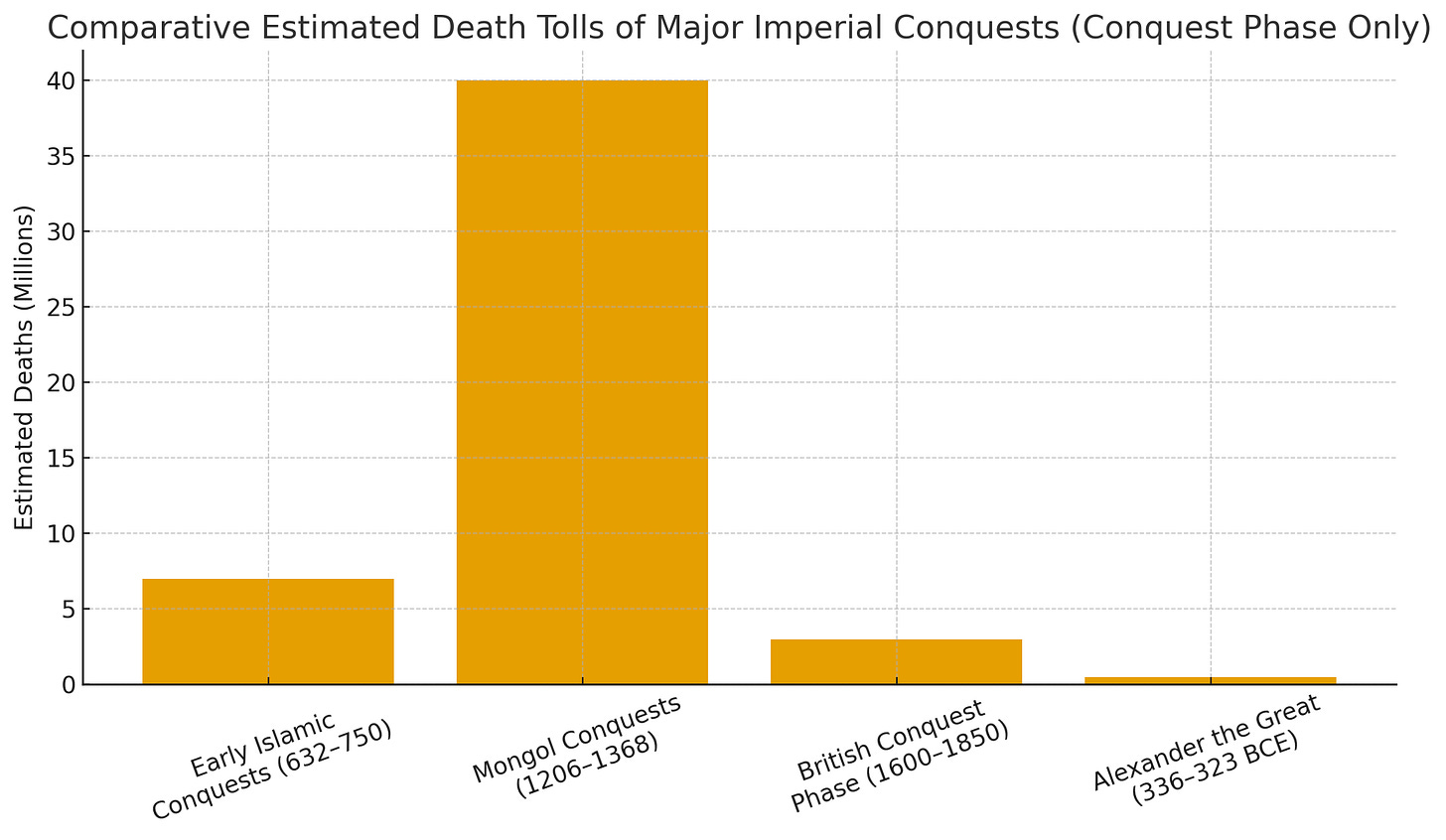

By raw speed, no empire except the Mongols ever matched it; by geographic reach in so short a span, not even Alexander the Great’s incandescent rampage (which killed perhaps 300,000–500,000) comes close; by societal transformation, it rivalled the Mughal and Ottoman consolidations combined.

And if we insist on playing the accounting game modern activists adore, then the early Islamic conquests likely killed ten times more people than the entire British Empire did during its periods of active military expansion, and in a fraction of the time. Yet in today’s fashionable Western catechism of “settler colonialism”—a sermon that demands endless self-flagellation for European sins—this world-altering imperial convulsion is treated as a polite cultural diffusion, or worse, ignored entirely.

My intention is not to indict modern Muslims for the actions of their distant ancestors; no sane person holds a twenty-first-century citizen morally liable for seventh-century events. But if we are going to moralise about conquest—which everyone seems eager to do—then intellectual honesty forbids the childish pretence that only Europe built its civilisation with the sword.

There is a temptation in certain modern circles to pretend that Islamic expansion was a kind of missionary ramble: an enlightened caravan bearing tolerance and poetry across a grateful world. Others, naturally, paint it as an apocalypse unique in its cruelty. Both versions are nonsense. What occurred between the seventh and tenth centuries was a conquest — vast, fast, and often as violent as any conquest in antiquity. It forged empires, ended civilisations, uprooted languages, and produced new ones. And like all conquests, it left behind a residue of transformation so complete that we sometimes forget a different world ever existed.

Consider, for a moment, the lands that Islamic armies encountered. Syria, Egypt, and North Africa were not deserts waiting to be filled with new revelation; they were heavily Christian. Egypt was, by all credible accounts, overwhelmingly Christian — Coptic Christianity being one of the oldest strains of the faith.

Syria was the beating heart of Aramaic-speaking Christianity. North Africa produced Augustine, the greatest theologian of the early Church. Iraq was a mosaic of Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, and assorted sects whose names barely survive beyond the footnotes of ecclesiastical history.

Persia was Zoroastrian — sophisticated, literate, imperially confident. Spain was a Visigothic Christian. Central Asia was home to Buddhism, Hinduism, and animism. The Arabian Peninsula itself was a mixed collection of pagans, Christians, and Jews.