Learning Krav Maga

From Auschwitz to Krav Maga—why I fight, and why the Jews must never stand alone again.

If you give even half a damn about free speech, subscribe. It means I can continue doing this without needing to ask a gender-neutral AI for spare change. I’m a suspended university professor, not a pundit barking from the cheap seats. The link is below, click it before the lawyers take it away.

Please subscribe to get at least three uncensored, impolite, fire-in-the-belly essays per week. Open comments, $6/month. Less than \ $4. Everyone says, “That’s just a cup of coffee.”

Well, then order mine.

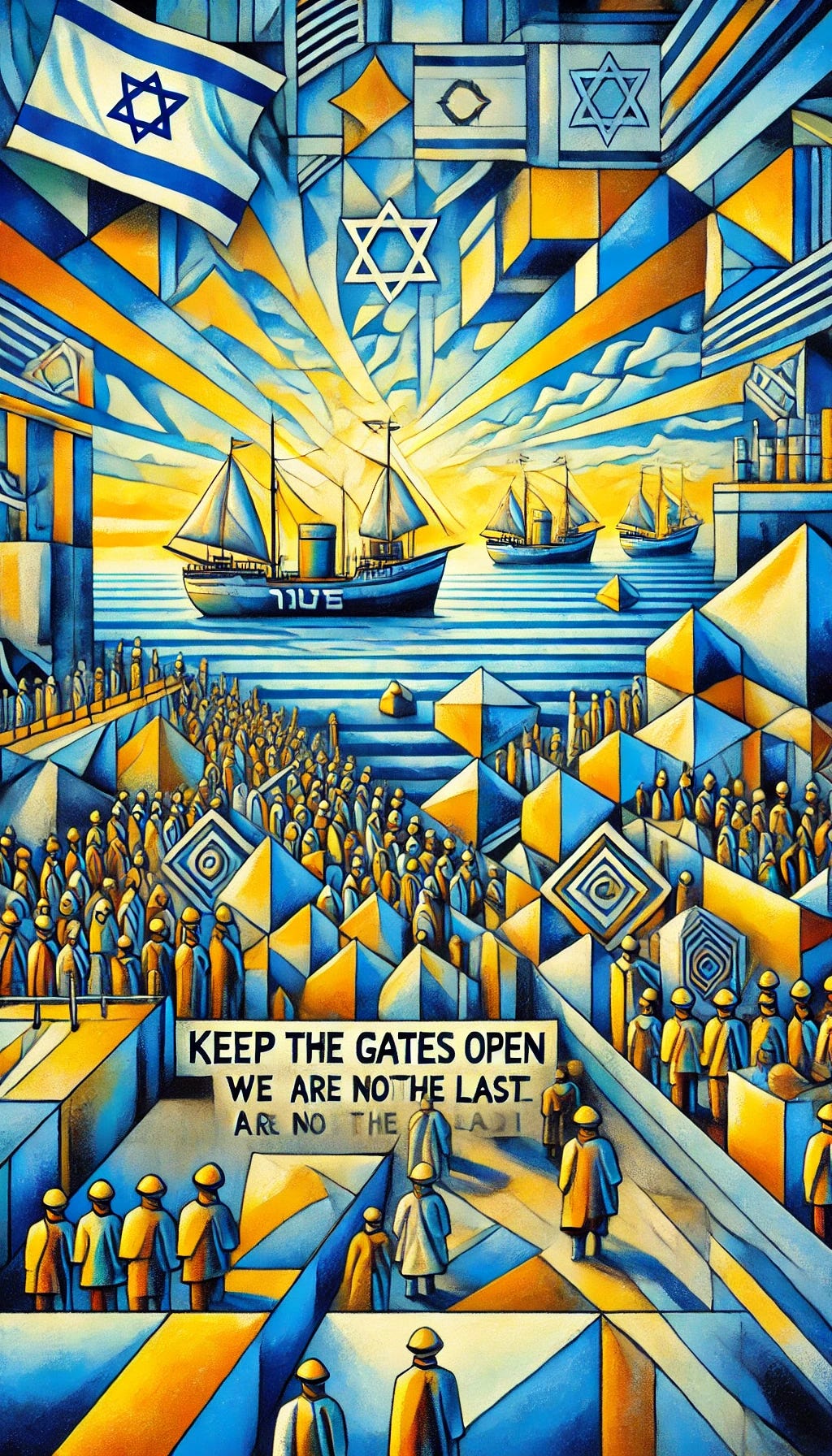

I’ve always been into Jews. Perhaps it began with a dog-eared copy of Exodus by Leon Uris, devoured in the bafflingly snowbound wilderness of Fort Garry, MB. Or maybe it was those biblically infused Sunday school tales: David, plucky and lean, standing defiant against the belligerent slab of Philistine flesh. The crowds, of course, were jeering. Until they weren’t, I was ten and already suspicious of majorities.

Even as a child, I waded—voluntarily—into books about the Holocaust. Others read about dinosaurs; I read about Dachau. I imagined myself, half-rescuer, half-John Rambo, smuggling stale crackers and sardines to imaginary Jews in a makeshift cardboard bunker in the forest behind our house. I hadn’t yet understood moral heroism, but I grasped the concept of shame.

After fleeing Winnipeg (a city that dreams of being duller than it is) at 19, I ended up on a farm in Switzerland. When given my first vacation, I did not opt for the carnal buffet of Amsterdam’s red lights like a normal young man. I went to Auschwitz and Dachau. Of course. I wanted to see the sign—the most brazen slogan in genocidal marketing: Arbeit Macht Frei. Work sets you free. A more honest phrase might have been 'Gas macht frei,' but history, like its tyrants, prefers euphemism.

I saw the tracks, the gates, the geometry of evil. Families led in like cattle. Some sent to “work.” Others became smoke.

Why wasn’t it my family clawing at the concrete walls, gasping in the dark, leaving chalk-white fingernails on the walls as their last protest? Why not mine? But then, they were unarmed, sleep-deprived, and marched by experts in sadism. They were not supposed to survive.

And so Israel entered the bookshelf next—not the Israel of hashtags and hashtags but of barbed-wire survivors turned farmers, turned pilots, turned warriors. I believed the Holocaust was now confined to the solemnity of textbooks. Surely, in a smug, liberal utopia like Canada, the idea of Jews needing refuge was academic, like Latin or chivalry.

But no.

“It’s like Germany in the ’30s,” said the father of one of my Jewish students. Not in a whisper. Not with panic. With flat resignation. The way you might note that rain is coming. They’d seen this film before. They knew the ending.

One week later, life imitated cliché. I was hauled into a cartoonishly small office by a grim-faced university administrator who handed me a suspension letter, much like a Soviet commissar might hand out a one-way train ticket. The crime? A post. Which post? “Was it the one where I said I stood with Israel?” I asked, with equal parts disbelief and snark. He wouldn’t say. He hadn’t read it. Didn’t need to. The scowl did the paperwork.

What followed was an institutional descent into derangement: gossip, faculty backstabbing, cowardly students with Wi-Fi and too much time. I was transformed—alchemised—from beloved professor to alleged thought criminal by the power of innuendo alone. And with it came the cascade: hate mail, lawyered letters, endless threats of “be silent or else”. I will not be silent.

What had once been my indignation hardened into betrayal, and then calcified into a rather bitter kind of calm.

Justice, it turns out, doesn’t always bend toward the good. Sometimes it loops like a Möbius strip, forever circling, never arriving.

I threw myself into amateur lawyering. It’s a miserable addiction, only slightly less destructive than meth and about as sleep-depriving. I taught elsewhere. I gritted through. But I needed something physical. Something absurd. Something with bruises.

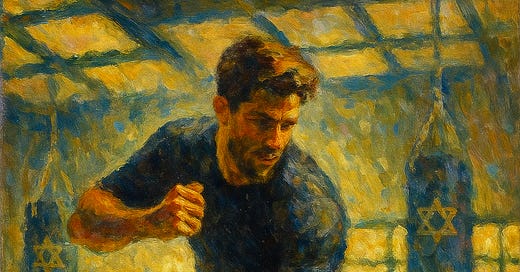

Krav Maga. Of course.

I’d spent so much time befriending Jewish strangers online that this seemed inevitable. Physical contact seemed preferable to philosophical self-immolation.

Now, as a child, I couldn’t do a jumping jack without looking like I was having a neurological event. Dancing? About as plausible as playing jazz flute on a trapeze. My last fight was in grade seven. I claim victory, but the historical record is, shall we say, fuzzy.

Sensei Mike was my guide into this violent ballet. He had a charmingly dictatorial habit of making me do pushups every time I said “sorry.” Which, as a Canadian, meant I lived on the floor. My training partner was a highly competent accountant whose wife had decreed they flee Canada due to—you guessed it—too much anti-Semitism. The final straw? The usual chant. The kind one hears on the streets of Toronto now with increasing regularity: Death to the Jews.

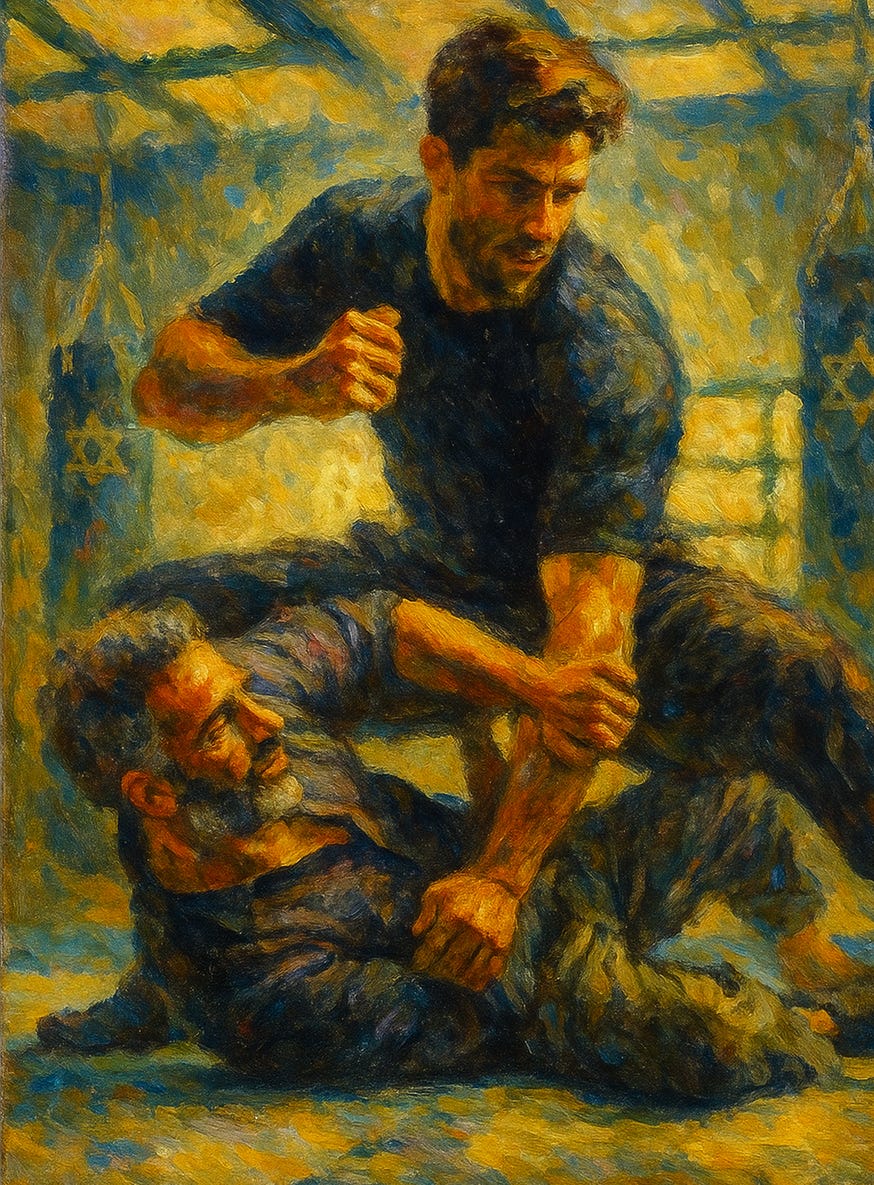

Krav Maga isn’t elegant. It’s violence by physics: elbows, leverage, momentum, and a grudging respect for bodily pain. I had to learn to roll before I learned to fall, and I managed to injure myself impressively just during warm-ups. Lesson two was delayed by a kidney stone the size of a chickpea—my ureter blocked like a Toronto bike lane at rush hour.

In a waiting room filled with half of Vaughan, each less visibly ill than the next, I learned a valuable lesson about the Canadian healthcare system: if you’re not dying, you’d better bring snacks.

But salvation, in the form of a Jewish urologist (of course), arrived with a laser and a plan. The stone was blasted into gravel. My inner plumbing was once again functional. And I was free to return to getting punched in the head by strangers.

Back on the mat, Mike was still patient, though his martial arts resembled teleportation more than combat. He could strike before my brain had even parsed the sentence “Incoming.” He said he’d trained the IDF. I believed him. I still believe him.

Most people in the class were Jewish. I liked that. I liked their seriousness, their history, and their necessity. I still think most of them could break me like a twig. Will I ever actually use Krav Maga? Not likely. If I were wise, I’d probably take a course called Not Starting Fights with Maniacs. Or Level Four: Avoidance and Strategic Cowardice.

But Mike made it clear: Jews don’t offer classes in Advanced Keeping Your Damn Mouth Shut.

So I’m back to elbows and sweeps and worrying about eye gouges. I still do pushups when I say sorry, and I still plan to go to Israel. When this university charade finally ends—if it ends—I’ll go. Not because I’m looking for peace. But because I’m still, somewhere deep down, that boy in the woods, imagining a cardboard shelter, hiding the ones who need it.

My children are now the same age I was when I stood alone at Auschwitz and wept. I am not a Jew, but how does that matter? Cain once sneered, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” The answer is yes.

Yes, I bloody well am.

Today, when I mention Israel to a doctor and watch her spine stiffen like she’s bracing for infection, when I see my faculty, unions, and students respond to my support for Israel with the indifference of the morally sedated, I no longer wonder if antisemitism is alive—I see it thriving.

It’s there in the street chants—“Go back to Poland,” they yell, ironically unaware that the Jews who were in Poland were already sent to the ovens. And it flourishes among the bureaucratic class—the latte-and-lanyard crowd—who gossip in hushed tones and say “those Jews” as if the phrase itself isn’t soaked in millennia of blood. But fear not—they wear pins and attend inclusivity seminars. How could they possibly be antisemites?

I see it in the eyes of the campus masses—those carbon-neutral angels of progress—who doubt the Holocaust ever happened or hedge it with euphemisms. The numbers are growing. That should chill us more than any winter in Warsaw.

Forty years ago, I knelt and ran my fingers along the grooves in the stone—grooves, my guide said, where the blood of Jews was sluiced away. I stood on the very tracks that carried men, women, and children to death. And now I watch in horror as that same evil, once spoken in guttural shouts, resurfaces in clipped academic tones and bureaucratic silences.

This isn’t a warning—it’s an indictment.

Antisemitism, that ancient and adaptable parasite, has not been eradicated. It has metastasised into smug activism and weaponised compassion. It no longer wears jackboots. It wears “Free Palestine” scarves woven in the hypocrisy of selective outrage and silence on Jewish death.

But I remember. I remember my father, recently buried, who, though not Jewish himself, would never allow even a whisper of antisemitic slander to pass unchallenged. I remember Dachau’s ruins, and I remember the bloodstained stones, and I know the obscene foolishness in believing “it can’t happen here.”

It can happen here. It is happening here.

Surely, the blood of every Jew murdered in the Holocaust, every soul torn from the world in pogroms, and even now—of Yaron Lischinsky and Sarah Milgrim, slain on our watch—rises like a chorus of red flares from history, screaming not to be forgotten.

We say “Never again,” as if repetition were a defence. It isn’t. Vigilance is. Memory is. Strength is.

Reason, alas, is not always enough. And this—this—is why we need a strong Israel. Because in a world where evil learns new languages and dons new disguises, some truths must be defended not just with words, but with resolve—and, if need be, with fire.

If you found value in this article and wish to support my ongoing work, especially during my 18-month suspension, please consider leaving a tip. Your support helps me continue producing uncensored content on critical issues.

I enjoyed this post. Stay fit, continue to exercise, and if learn evenone thing from your Krav Maga classes, learn that one thing well. To quote Bruce Lee, "I don't fear the man who has learned a thousand different kicks, I fear the man who has learned one kick and practiced it one thousand times."

Thank you. You have brought great comfort to this Jew in San Francisco.