No, Our Kids Are Not OK

A Cry from the Heart of a Reformed Libertarian and a Parent

We do not hide our children in attics anymore, but we have perfected a far more sophisticated concealment — one built from embarrassment, comparison culture, and the quiet terror that our private suffering will be measured against the curated triumphs of others. The hiding now is digital, polite, and entirely respectable. It happens behind smiling profile photos, carefully worded updates, and the collective agreement not to say aloud what too many of us already know.

Spend any evening among parents of university-aged children, and you will hear the same liturgy, recited with serene confidence: the future doctor, the future lawyer, the child already glowing with promise. These declarations are not always born of arrogance. Often they are defensive — a way of keeping pace in a culture where parenting has become a public performance, and failure feels like a moral indictment.

In the age of social media, silence itself is suspect. To say nothing is to invite speculation. To admit struggle is to risk judgment. So we perform reassurance instead. We rehearse success. We pretend the story is still on schedule.

What you almost never hear is the harder truth: my child is collapsing; something is happening inside their mind, and I cannot name it, measure it, or stop it. The decline does not announce itself with drama. It creeps in through isolation, sleeplessness, withdrawal, rage, panic, and an uncanny flattening of joy. While each family experiences it differently, the pattern recurs with unnerving consistency.

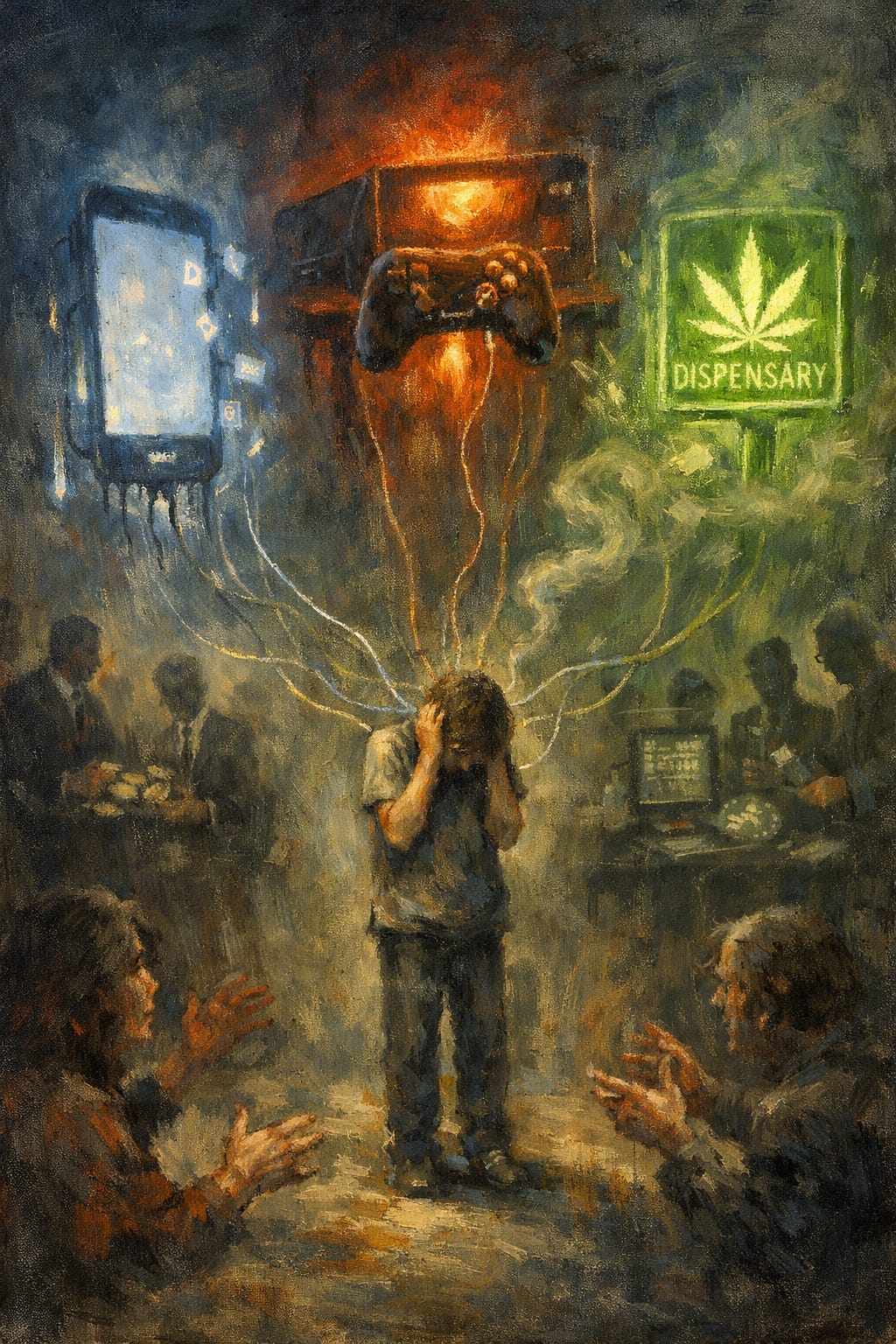

Three forces now converge on the developing brain with unprecedented intensity: high-potency THC, algorithm-driven social media, and immersive video gaming. Each is legal. Each is profitable. Each is defended in the language of choice. And each operates on the same neurological circuitry — dopamine, reward, reinforcement — in brains that are not yet finished forming. This is not conjecture or generational panic. It is the basic architecture of human neurodevelopment colliding with markets optimised for compulsion.

Parents know something is wrong long before the data arrive. There is only intuition, dread, and the slow realisation that willpower is no match for systems engineered to capture attention indefinitely.

The problem is not that some children struggle; that has always been true. The problem is scale, intensity, and denial — and the lie we tell ourselves that because our own child appears intact, the danger must be exaggerated.

These stories are everywhere, but they circulate quietly because pain resists exhibition. Parents do not boast about diminished futures. They do not post congratulatory updates about the collapse.

Silence here is not always deceit; often it is grief.

There is also the small technical problem that no parent possesses a neurological testing lab in the kitchen. You cannot swab the prefrontal cortex before dinner. You cannot measure dopamine dysregulation between errands. Instead, you rely on instinct — the oldest diagnostic instrument we have — and millions of parents feel it now: something is wrong.

Because the suffering is private, we commit the laziest statistical error imaginable: we assume that what we do not hear must not exist.

The numbers disagree.

Across much of the developed world, youth anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicidal ideation and the act itself have risen sharply enough to strain mental-health systems.

Researchers increasingly distinguish between ordinary digital use and addictive patterns — craving, distress when restricted, loss of control, interference with daily life — and it is the latter that correlates strongly with worse outcomes.

Longitudinal studies following adolescents over the years show that high or rising trajectories of addictive social-media and mobile-phone use are associated with markedly elevated risks of suicidal thoughts and behaviours compared with low-use peers. This is not a cultural hunch. It is a measured association.

At this point, an inconvenient fact must be stated with clinical clarity: children are not neurologically interchangeable. They do not start from the same place.

Genetics accounts for a substantial share of vulnerability to depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia-spectrum illnesses, ADHD, and substance-use disorders; environment then layers itself onto this biological scaffolding, sometimes buffering it, sometimes detonating it.

In plain language, some children are born closer to the cliff’s edge than others. This is not ideology. It is behavioural genetics.

Which makes the familiar refrain — my child is fine, so don’t impinge on their freedom — not merely selfish but mathematically illiterate.

Public policy is not designed around fortunate anecdotes or the comfortable median. It exists because of the tails of the distribution curve. When a society knowingly saturates the environment with high-dopamine stimuli and psychoactive substances, it is not the robust who concern us. It is the neurologically susceptible — the statistical outliers parents don’t brag about — who pay the price.

Intelligent people revise their beliefs when evidence intrudes. Only ideologues cling to abstractions once reality has rendered its verdict. So let me state this plainly: I am no longer a libertarian.

Before anyone imagines that this conclusion was reached during a late-night screening of Reefer Madness, let me be explicit. I initially supported marijuana legalisation. I arrived there calmly, convinced that adults could be trusted to behave like adults. I did not clutch pearls. I did not confuse a guitar solo with civilizational collapse.

I was wrong.

At this point, someone invariably raises the ritual objection: what about alcohol? And yes — empirically, alcohol is more destructive. A society without it would likely be healthier. But some genies cannot be forced back into their bottles, and two wrongs do not make a right.

The existence of one long-standing harm is not an argument for licensing new ones, especially when the new harm is being deliberately optimised for the neurologically unfinished.

Civilisation does not progress by multiplying its poisons and calling the result freedom.

And to avoid sanctimony, I will add what should not need to be added. As far as weed? - I am no stranger to the substance. I have smoked it, vaped it, tried it in blunts, joints, and edibles — sampled the modern cannabis menu with sufficient thoroughness to disqualify myself from the temperance movement.

I simply discovered that I do not enjoy being high. The experience struck me as mental fog with delusions of insight. So I stopped. Others do not. Some cannot. And it is precisely those people — especially the young — whom a serious society is obligated to protect.

Others do not stop.

And this is where libertarian optimism collapses. The issue is not that marijuana exists; the issue is that some people love it too much — and when those people encounter today’s high-potency products during adolescence, the consequences are no longer theoretical. Potency has risen dramatically over the past three decades. When the drug changes, the risk profile changes — especially for developing brains.

Psychiatric research now consistently links adolescent cannabis use with increased risk of psychotic outcomes, particularly among early and frequent users, and notes that a substantial proportion of those who experience cannabis-induced psychosis later develop chronic psychotic disorders.

If a nontrivial minority of the population is genetically closer to psychosis at baseline, saturating youth culture with higher-potency cannabis is not liberal tolerance; it is a neurological gamble.

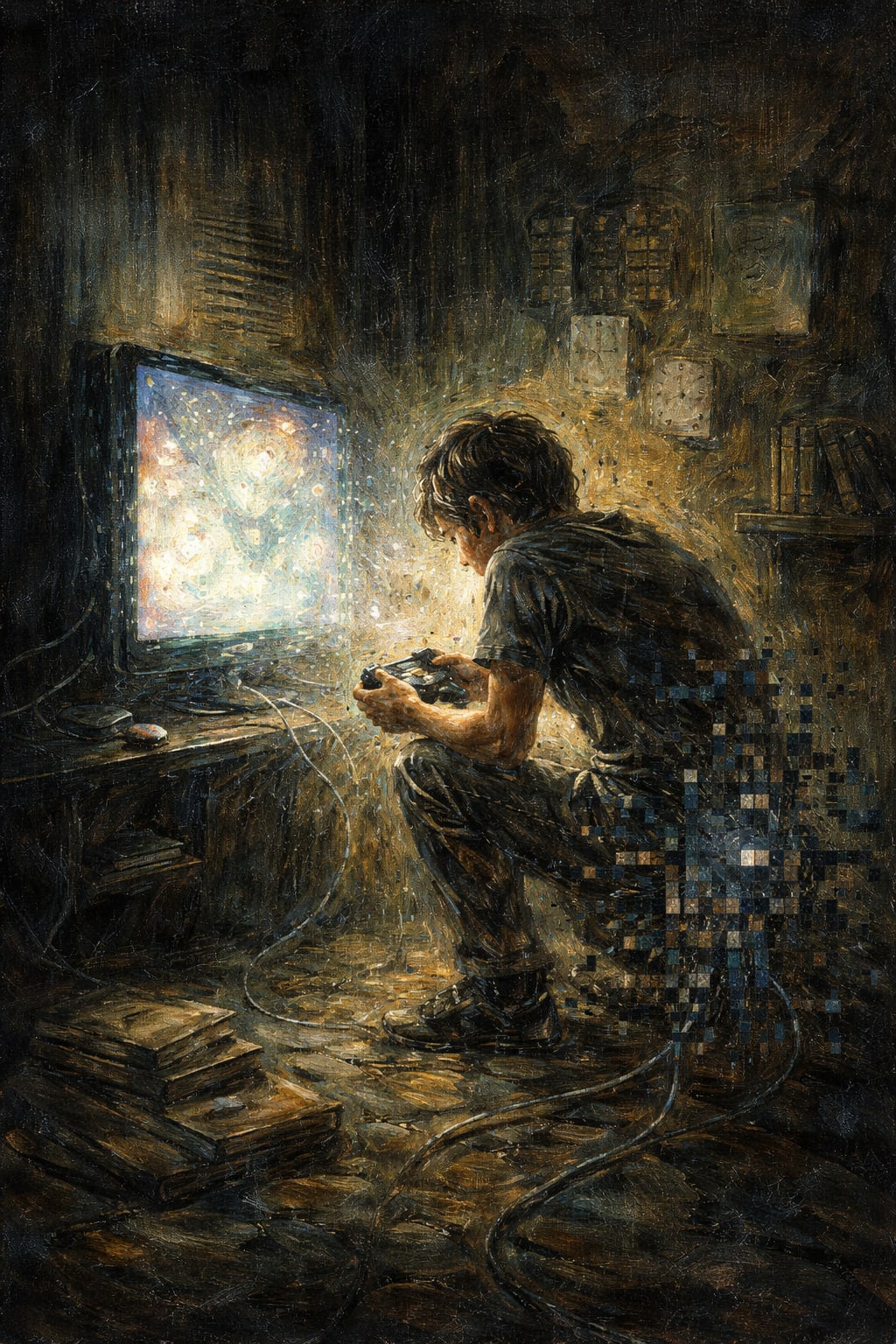

Social media, though less chemical, is no less neurological. These platforms are not neutral town squares; they are engineered environments optimised to capture attention through intermittent rewards, social-validation loops, algorithmic novelty, and endless scrolling. Their core metric is not flourishing; it is time on platform. When researchers separate compulsive use from casual use, the picture sharpens: it is dependency — not mere minutes — that predicts harm.

Parents see this long before institutions admit it. Yet how are parents supposed to assess neurological damage? There is no warning light announcing eroded impulse control. By the time the signs become unmistakable — collapsing attention, emotional volatility, social withdrawal — the architecture may already be shifting.

The prevailing advice that parents should simply “manage it” borders on unserious. Install blockers. Set limits. Monitor usage.

Such counsel assumes households can outmanoeuvre trillion-dollar persuasion machines designed by behavioural scientists whose explicit task is to capture attention. Blocking software is defeated with embarrassing ease. Platforms evolve faster than safeguards. Peer culture overwhelms household authority. Once the child leaves home, parental leverage evaporates.

Expecting families to counter industrial-scale behavioural engineering is not policy. It is abdication disguised as virtue.

The market cannot be trusted to self-correct because the market’s loyalty is to profit. Many senior figures in the technology sector quietly restrict their own children’s access to the very platforms they champion publicly — an admission more eloquent than any white paper. The architects understand the machine perfectly well.

Public institutions have not distinguished themselves either.

Universities and colleges increasingly behave like revenue-dependent enterprises. Rather than defending disciplined attention, they adapt to its disappearance: standards soften, grades inflate, expectations decline, and tuition continues to rise. When institutions entrusted with intellectual formation cease defending the conditions necessary for thought, they are no longer merely failing; they are participating.

The cultural defence of all this rests heavily on anecdote.

Someone invariably announces that their child scrolls endlessly, plays games constantly, perhaps uses marijuana, and is nevertheless thriving. Excellent. Public policy, however, is not written for fortunate exceptions.

It exists to protect those at the margins — the adolescents whose neurochemistry proves less forgiving. Airbags are not installed because most drivers crash. They exist because some do.

There is also a generational hypocrisy worth naming.

Many older adults dismiss these concerns because they themselves emerged unscathed from youth. I am in my early sixties; social media did not arrive until my brain had finished developing. To wave away contemporary harms on the grounds that earlier generations survived is not wisdom. It is historical luck masquerading as judgment.

Over the past two years, I have written publicly about my own professional collapse — about being dismissed from my career after stating openly that I stood with Israel, about watching decades of work evaporate.

Many readers have followed that story.

But let me now say something more important than any professional ruin. Every parent understands this instinctively: I would give away my career, my financial future, and every marker of my own success without hesitation if it meant my child could simply be well.

And my child is not well.

This piece is not about me, and it is not about them.

It is about the millions of families living in this quiet emergency. No. This cannot continue.

What would seriousness look like? Not prohibitionist hysteria. Not authoritarian fantasy. Simply the restoration of guardrails, any civilisation claiming to care about its young should already have in place. Devices sold to minors must ship with hard, default restrictions that cannot be casually bypassed and that require verified adult authorisation to remove.

And even as we struggle to erect these basic protections, a familiar chorus begins again — this time on behalf of psychedelics. LSD. Psilocybin, the sanitised clinical name for what used to be called magic mushrooms. We are told, with the same breezy confidence that once accompanied high-potency cannabis, that these are harmless, even enlightening substances — tools for recreation, perhaps even vehicles for personal growth. The language is always identical: relax, it is safe; do not be prudish; do not be alarmist.

We have heard this before.

A serious society does not abandon its moral axis simply because enforcement is imperfect. The argument that “they will do it anyway” is not wisdom; it is surrender disguised as sophistication.

Laws are not merely instruments of control — they are declarations of judgment. To call something illegal is to say, publicly and without embarrassment, that it carries risk, that it harms, that it destroys more lives than polite advocates care to admit.

So when the push comes to normalise yet another class of consciousness-altering drugs, let us speak plainly about motive. This is not a crusade for liberty. It is not a humanitarian awakening. It is a market opportunity.

There is money to be made.

That is the engine. That is the incentive. And history has already shown what happens when profit discovers the malleable brain: hesitation evaporates, caution is rebranded as fear, and the burden of consequence is quietly transferred to families.

A civilisation that cannot draw lines will eventually forget why lines existed at all.

Guardrails are not signs of panic. They are signs of adulthood.

Serious reform must also give parents tools that actually work. Hard gaming blockers — not cosmetic settings easily bypassed by a fifteen-year-old with a YouTube tutorial — must be standard, enforceable, and durable, available to parents as a right rather than a premium feature.

Classrooms must again become defended spaces: phone-free environments treated not as oppression but as educational hygiene, no different in principle from banning cigarettes or enforcing quiet during an exam.

Reliable THC testing kits must be readily available to parents who want to know what is entering their homes, without stigma and without bureaucratic obstruction. And age thresholds for social-media access — under sixteen at minimum — must be enforced, not winked at, not outsourced to self-reporting forms that insult the intelligence of everyone involved.

None of this is radical. It is merely what a society does when it decides that children matter more than quarterly earnings.

And above all, liability must enter the conversation. Someone needs to be sued into the ground. Money is all they care about; they hate our youth, let us litigate them into dust.

Industries change their behaviour when they are compelled to absorb the costs of the harm they help generate. If companies will not build tools that actually protect children, then they must be sued until inspiration arrives. Litigation is not cruelty; it is accountability.

We did not reform tobacco by asking politely.

Some families can enforce these standards on their own. Many cannot, particularly single-parent households already stretched thin. Public policy exists precisely for such asymmetries — to ensure that protection does not depend entirely on private strength.

At some point, a civilisation must decide whether it values the developing brain enough to defend it. Freedom remains one of liberal society’s great achievements. But freedom without guardrails, especially for the neurologically unfinished, is not liberty. It is abandonment.

There must be outrage. There must be fury. And again, there must be litigation.

We must protect our children — especially those nearest the cliff, the ones whose suffering is private, the ones parents do not brag about. History will not forgive a society that knew what was happening and chose comfort over courage.

No — our children are not OK. And pretending otherwise is the most expensive lie we have ever told.

If you say, “My children are well, thank you,” I hope that this is true. I do not wish harm on anyone.

But a society cannot rest its conscience on the luck of the fortunate and then tell the rest to fend for themselves.

“My household is fine” is not a moral position; it is a statistical coincidence elevated to a philosophy.

This is the oldest evasion in human history.

When Cain is asked where his brother has gone, he replies with the line that has echoed through every age of indifference since: Am I my brother’s keeper?

The question is intended as a deflection, narrowing moral responsibility to the smallest possible radius. It is also the question every comfortable society asks when faced with suffering it did not personally generate.

The answer, whether one takes the story as theology, literature, or moral archetype, is obvious. Yes. We are. Always have been.

A civilisation that shrugs and says, “My children are fine, so the rest of you go sort yourselves out,” has already abdicated the very idea of shared responsibility. Public health, education, and child protection have never operated on the principle that only the vulnerable should concern themselves with vulnerability. If that were the rule, seatbelts would be optional for the skilled driver, vaccines unnecessary for the healthy child, and guardrails removed because most people don’t fall.

The children most at risk — those in the tails of the distribution curves, those with greater neurological fragility, those whose genetic or psychological starting points leave them less buffered against addictive systems — cannot be protected by their parents alone. Not against trillion-dollar industries designed to capture attention, normalise dependency, and monetise breakdown. To leave this burden solely on exhausted, grieving, and often isolated families is not compassion. It is moral outsourcing.

Parents of children who are doing well must join this fight precisely because they can. They have social capital, political leverage, and the luxury of bandwidth. Silence from them is not neutrality; it is consent. Every time a comfortable parent dismisses this crisis because it has not entered their living room, they strengthen the hand of those profiting from harm.

And let us be clear about the adversary. This is not about individual weakness or parental failure. It is about systems that deliberately extract value from neurological vulnerability. They are monetising our children’s neurological breakdown — and they will continue to do so until they are forced to stop.

This will not end with polite requests, nor with glossy pamphlets urging “awareness,” nor with the seasonal guilt campaigns that flutter briefly across the public conscience before vanishing into the algorithmic abyss.

It will end only when a society decides — with the cold seriousness such a decision demands — that children are not acceptable collateral damage in a market experiment. It will end when outrage gathers into something immovable, when regulation ceases to be negotiable, and when litigation becomes so unsparing that those monetising our children’s neurological breakdown discover, at last, that exploitation carries a price.

Do not step onto the porch expecting to hear the prayers. Ours is not a theatrical age; suffering rarely announces itself with trumpets. These prayers are whispered into darkness, breathed into pillows damp with exhaustion, spoken in kitchens long after midnight by parents who have forgotten what unbroken sleep feels like.

But they rise nonetheless.

“Lord — spare my child.”

“Bring them back to me.”

“Let tomorrow not resemble today.”

Hear mine. Hear my neighbours. Hear the prayer of the mother who has learned to dread the sound of her own telephone. Hear the father sitting beneath the sterile light of an emergency corridor, staring at a wall because hope requires somewhere to rest its eyes.

We do not require unanimity; societies never do. What we require is solidarity — especially from those whom fortune has spared the worst of this storm. For a people cannot say, “My children are well,” close the door, and leave others to keep vigil alone. That is not citizenship. It is a refined form of indifference.

If protection is left only to the parents already drowning, it will never be enough. The strong must not merely congratulate themselves for surviving; they must step into the water.

No — our children are not OK. And the question before us is not whether they are ours in the narrow arithmetic of blood, but whether we possess the moral seriousness to act as though they belong to all of us.

History does not remember societies for their wealth, nor for their cleverness, nor even for their freedoms. It remembers them for what they permitted to happen to their young.

Because a society is revealed, finally and without appeal, by the children it refuses to lose — and by the ones it does not bother to save.

So let us retire, once and for all, the ancient question. Do not ask whether you are your brother’s keeper. Ask instead what kind of people we become if we decide that we are not.

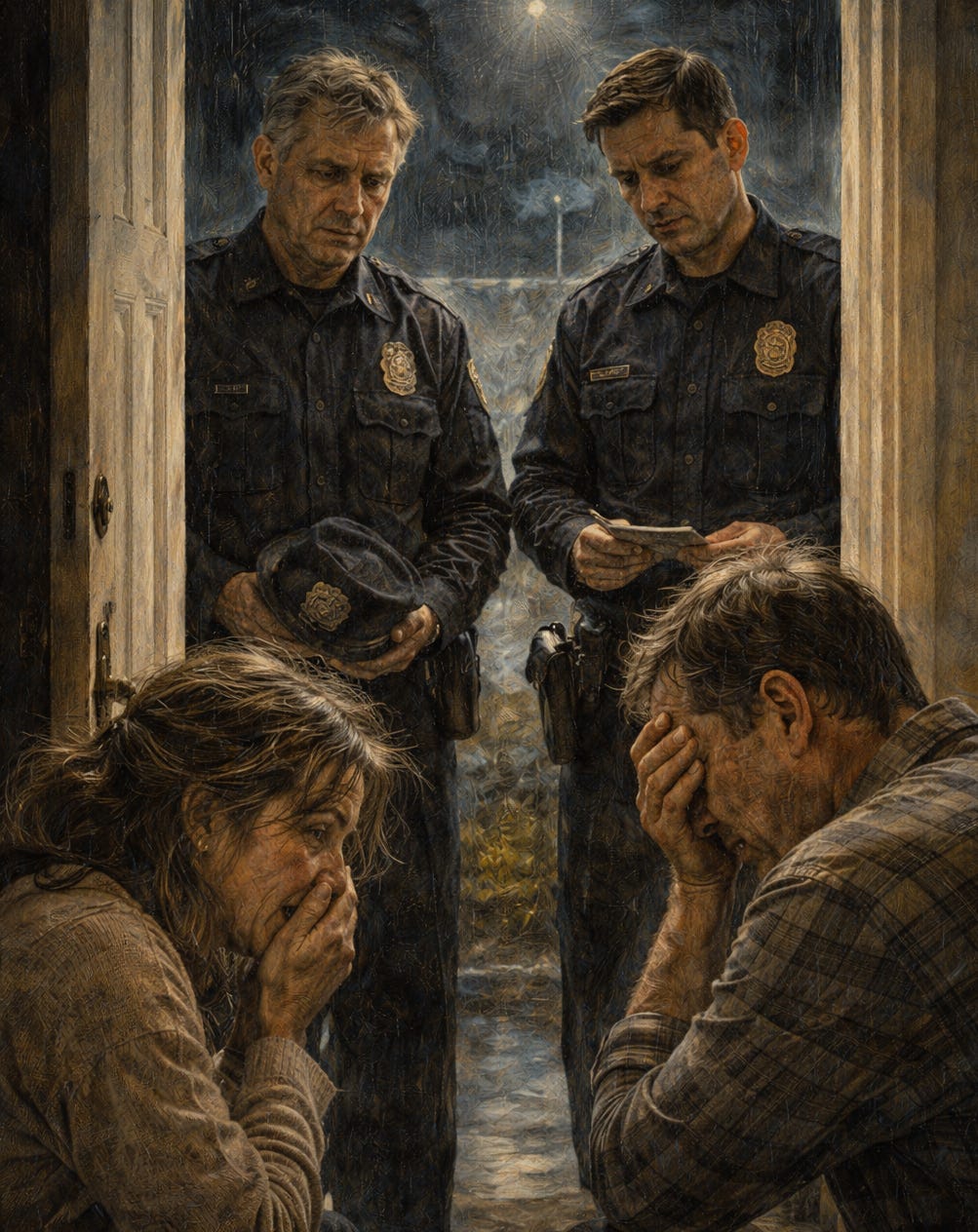

And before you answer too quickly, ask yourself another question — one that visits far more parents at night than anyone admits aloud: how many of you lie awake wondering whether there will someday be a knock on the door?

Two police officers are standing on the porch. Faces composed in that terrible professional calm. And you have no idea why they are there — until they tell you your child is gone.

In that instant, the world does not merely dim; it collapses. The clock continues to tick, but time itself loses meaning. And the pain does not recede with the seasons. It settles in. Permanently.

That is the quiet terror many parents now live with: What is happening to my child? Have I already lost them in ways no one can yet measure? Will I see the warning in time?

Meanwhile, we permit corporations to monetise our children’s brains with something approaching impunity. High-potency THC. Dopamine-engineered platforms. Gaming environments designed with casino-level behavioural psychology.

Vast industries feed on neurological vulnerability while wrapping themselves in the soothing language of “safety tools,” “parental controls,” and “community standards.”

Do not be fooled. Public-relations departments are not guardians of your child. Sponsorships are not safeguards. Optional settings buried three menus deep are not protection.

They know precisely what they are doing.

When a business model depends upon compulsive engagement from the neurologically unfinished, deception is not an accident — it is a strategy.

Call things by their proper names: these are not merely negligent actors drifting through a regulatory grey zone. They are predators of attention, devourers of developmental time, merchants operating in a marketplace where dependency drives revenue.

And they must be stopped!

Not nudged. Not politely petitioned. Stopped — by regulation with teeth, by litigation that makes exploitation financially suicidal, and by a public unwilling any longer to accept the slow neurological auctioning of the young.

Because a society is revealed, finally and without appeal, by the children it refuses to lose — and by the ones it does not bother to save.

I once faced a student who told me, quietly and without drama, that his eleven-year-old sister had taken her own life. I stood there, nodded, said something inadequate, and then went on to teach my class as if the room had not tilted on its axis. I barely made it through the hour.

Later, alone in my office, I wept.

There was no lesson plan for that moment. There is no training for it. There is only the knowledge that something has gone catastrophically wrong, and that polite abstractions about “choice,” “screen time,” or “risk tolerance” collapse into obscenity when set against a child’s grave.

God save us.

Please share. We need to start a revolution.

A very powerful and truthful reflection on the deliberate devastation of our youth.

I think most people feel they're being conspiracy theorists for articulating their fears that money is behind the algorithms and liberation of drugs and other harms, like teaching children they can change sex.

Your essay makes it clear that it isn't a conspiracy theory, its an awakening.

Wow! Brilliant expose! Thank you, @PaulFinlayson.... kol ha'kavod!