The Stink of Bitterness. A lesson from Mr. Gotz. And Masha.

How betrayal, silence, and Elly Gotz, a Holocaust survivor, helped me choose a better path. Masha is my cat. Not related to Mr. Gotz.

If you believe in the importance of free speech, subscribe to support uncensored, fearless writing—the more people who pay, the more time I can devote to this. Free speech matters. I am a university professor who was suspended for criticising Hamas - so I am not speaking from the bleachers.

Please subscribe to receive at least three pieces /essays per week with open comments. It’s $6 per month, less than USD 4. Everyone says, "Hey, it’s just a cup of coffee," but please choose my coffee when you come to the Substack counter. Cheers.

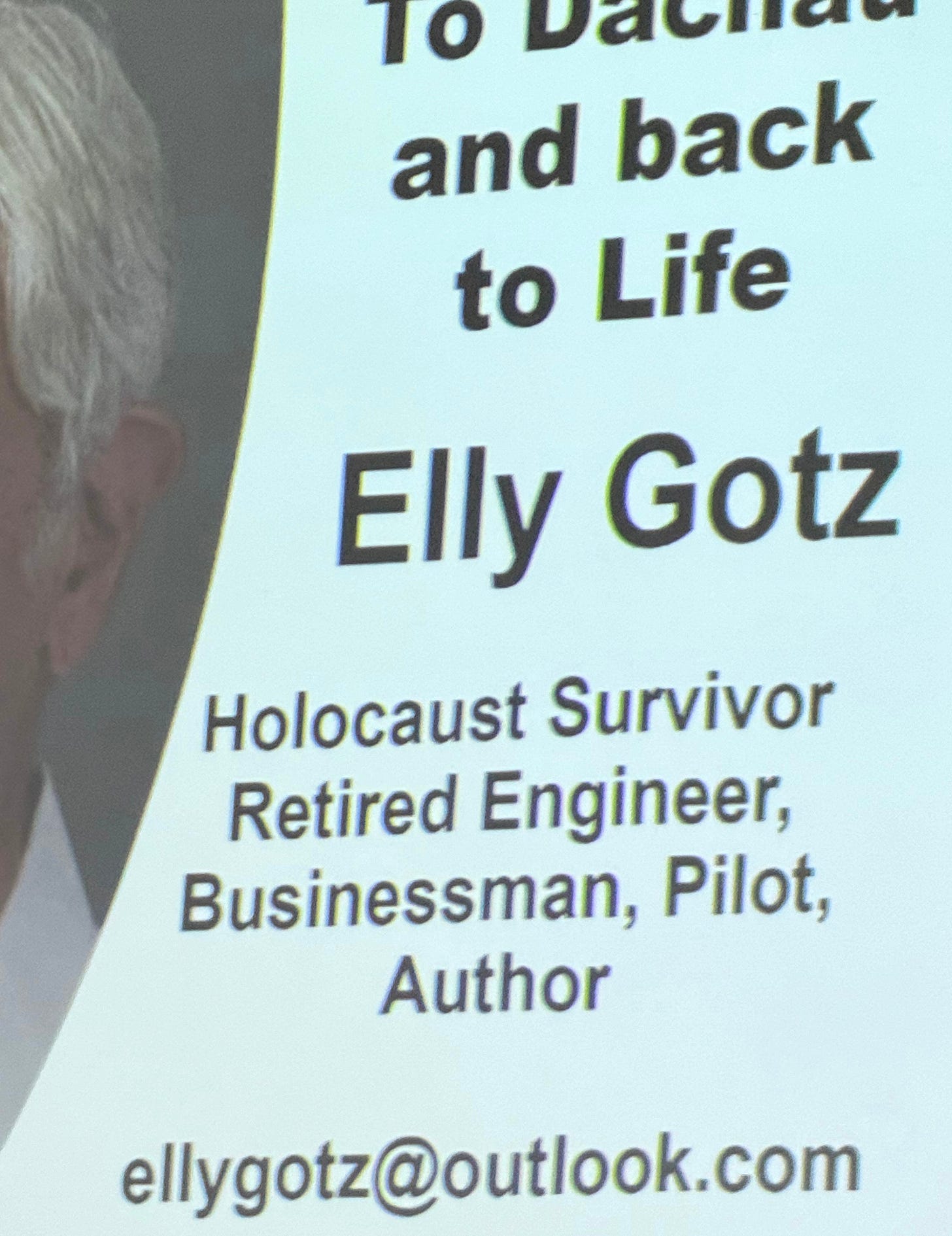

Elly Gotz is a Holocaust survivor. I will get to him at the end.

When I began this essay, I didn’t know my conclusion. I figured it would come to me. While I was angry at the Kafkaesque echo chamber that some unnamed, vindictive administrators had thrown me into—because I insulted a man who wanted Israel destroyed—I insisted I wasn’t bitter.

I was simply pursuing justice.

But it turns out the delusion I diagnosed in others had quietly signed a lease in my own mind.

When we suffer injustice, we wear it proudly; bitterness, by contrast, has no fashion appeal. But maybe I was blind. Bitterness had taken root—it fed me. It kept me standing: proud, erect, but also toxic and indigestible.

I leaned on words from Abraham Kuyper, the former Dutch PM, who said that when principles opposed to your convictions triumph, then battle is your calling, and peace becomes sin.

You must lay your beliefs bare before friend and foe, with fire and faith. I still believe this.

But even a righteous cause can grow bitter roots.

That is my lesson.

I told myself my angst stemmed from injustice. I believed that had I been meek from the start, I might have appeased the “Fire him now!” crowd—those digital zealots and cowardly administrators eager for my banishment. For standing up to bullies rarely helps your job prospects. Bullies sometimes dig grovelling.

But I feel no contrition for my comments. For those new here: I called Hamas Nazis. A fellow professor lost his mind, as if I’d defiled his family grave and sold the headstones as driveway gravel. He really liked Hamas.

The university’s decision to escalate this into a Human Rights Complaint—over a comment well within the realm of civilized discourse—was indefensible. Worse, they ignored the fears of Jewish students who watched a professor peddle antisemitic tropes, celebrate Hamas and the Houthis, and equate Jews, Israel, and evil in a single breath.

The university knew. They knew exactly what they were doing. They knew the wreckage they would unleash on my career, my family, the Jewish community at the university and their and my place in the community. And they did it anyway.

The decision to escalate a Human Rights Complaint over a statement clearly within the bounds of civilized discourse was indefensible—especially when they ignored the concerns of Jewish students. These students feared a professor who publicly pushed antisemitic tropes, celebrated Hamas and the Houthis. The university knew. They chose Hamas over Israel.

They knew the process would be the punishment.

Even with that clarity, and despite the change in my own tone, my mind has not gone soft. After eight months, I still have no idea if I’ll ever be allowed to teach again. The school’s latest move?

In July, 2024 I went to the union office - I went in person, I think today when we don’t do something digitally, we have to be clear.

The university made it sound like I had stormed the Bastille with a pitchfork and a manifesto, not quietly walked the same hallway I’d strolled thousands of times before. No raised voice, no disruption, no grand gesture—just a man trying to make sense of a Kafkaesque inquisition.

For this, they threatened to sic the police on me.

Let that sink in: a professor—suspended without explanation, denied process, answers, or dignity—returns to his own office to speak with his union rep, and the response is a couriered threat of criminal trespass. Not even a phone call. Not a conversation. Just lawyercraft delivered like a ransom note, drafted by some basement-dwelling legalist too gutless to look me in the eye.

It’s a symptom of a deeper rot: the replacement of courage with cowardice, of dialogue with digitized intimidation. Bureaucrats have become warlords of silence, enforcing power through auto-replies, unread inboxes, and the sterilized violence of legal threats.

I had knocked on the door of my own community, and they sent me a bark in legalese. That is not justice. That is theatre.

Absurd doesn’t begin to cover it. Nine months of banishment, and still no defence. The investigation is a farce—a parody of Nuremberg, with amateurs responding to an anti-Zionist’s rage because his fav terrorist group was dissed.

This whole saga could’ve been solved—easily—with decency, courage, and one man willing to say, “I was offended by what you said.” Instead, it became “Off with his head!”

If you zoom out far enough, it’s comedy. But from here, it’s exhausting. Marx said history repeats: first tragedy, then farce. Even he didn’t foresee this.

Someone was allowed—without speaking to me—to accuse me of being dangerous, of assaulting students, of racism, of Islamophobia. Lies piled on lies, aided by colleagues. I believed it was wrong in November 2023. I still do—more than ever.

But something has shifted—not in facts or conviction, but in spirit. Friends helped. Gentiles and Jews alike. Mostly Jews.

The summary again?

On Nov. 27, 2023, I was banished, suspended, slandered—because I wrote on LinkedIn to a stranger in Pakistan who called for Israel’s destruction. I said I stood with Israel. And if you stand with Hamas, you’re siding with Nazis.

The Nova music festival massacre had just happened. Filipina nannies, peace activists, and barefoot dancers were slaughtered. My daughter, if in Israel, might’ve been there. She might have been raped or killed. That haunts me.

My spirit has changed—but not my beliefs. It was a medieval slaughter. No justification.

Some told me to let the matter drop. to let the idiot gears of the university’s faux rage machine turn. To let it “ride out.” To confront injustice with acquinesence. To let their lawyers rage.

I didn’t realize that for some lawyers, lawyering is Cobra theatre: flaring out the hood, playing mind games, and dodging facts. I thought lawyers studied the law in university, but many seem to not have got out of pycho ops class.

Highlighting the abuses of their own policy—it was futile. No one cared. I assumed facts mattered. I thought lawyers needed to know the case. Turns out, many don’t.

But after eight months, I no longer wanted to be called “bitter.” I insisted I was righteously angry. Not bitter. Just triggered.

Then I began to realize something.

Bitterness wears many masks. It distorts your view of reality. It stains those around you. Even if it starts as righteous rage, it can rot you. Maybe I was just another goat-evicting temple flipper, convincing myself I was some biblical reformer.

We see bitterness more clearly in others. When a friend complained endlessly about his mechanic, I felt no sympathy, in my head I thought, “get over it.”

Then someone told me I needed to move on. That stung more.

I thought I was like the suffragettes or abolitionists—committed to justice, not bitterness. But even that idea reeked of grandiosity.

Proverbs says every heart knows its bitterness. I was beginning to know mine.

If you want to protest injustice with a clean heart, you must focus on reconciliation, not revenge.

Bitterness is being jaded. It’s believing everyone’s out to get you. And when institutions ignore your emails, pretend your policies don’t exist, or reply with lawyer-speak designed to shut you up, bitterness grows.

And digitization doesn’t help. Emails can be ignored, texts ghosted. Everything’s passive-aggressive. Digitization empowers the coward. Defamers thrive in digital spaces.

In a university human rights tribunal, evidence barely matters. Adjudicators pick a side—who they “like” better. Lies stick. Gossip spreads. And you never know who believes what.

You can’t walk around saying, “Hey, if you heard I was a pedophile, it was a lie.”

People just walk past you, and you wonder.

I lost not just my job—but the micro-community I loved. The cleaner, the security guard, the cafe lady, the student who nearly made the NHL. All gone. Overnight. And less than 1% reached out.

The relationships were shallow—but real. And their disappearance hurt.

Ben Franklin said, “Justice will not be served until those unaffected are as outraged as those who are.” No one was.

The Buddha supposedly said bitterness is drinking poison and hoping your enemy dies. On July 22, I had gone back to campus to reclaim some agency. I wanted people to look me in the eye. But that didn’t work out.

Bitterness has roots. It grows deep. But bitter roots don’t nourish justice. They only grow bitterness.

My father was a farmer. Roots matter. Barley grows barley. Wheat grows wheat.

I wondered if a root could nourish both bitterness and justice. My grandfather would’ve told me to eat healthy and drop the philosophy course.

Bitterness leaves a stain. My birth father died alone—estranged from everyone. I never met him. I don’t want that.

I can’t let bitterness ruin me or poison my children.

I want to live like my adopted father—a good man, a professor, shaped by Depression-era poverty but full of hope.

Bitterness is a Solvent of the Soul

The Greeks had a word for it—pikría—bitterness that doesn’t merely sour the heart, but stains everything it touches. A spiritual rot with a splash radius.

I’m adopted. My biological father, as I know him, lives only in family lore. He died in 2003. His funeral, I’m told, was sparsely attended. He denied paternity when it came to my twin brother and me, yet somehow took offense when our mother gave us up. That, apparently, was his wound to carry.

He cut off his entire family. Died alone. And I’ve often wondered: was it bitterness that consumed him?

By sheer coincidence, I once worked in Arizona—just miles from where he lived. Never met him. Never spoke. That silence is its own inheritance. That is the stain of bitterness.

I have indulged bitterness myself, convincing myself that it was only about injustice. That my anger was righteous. But one doesn’t need a therapist to know: the pursuit of justice and the infection of bitterness are not the same pilgrimage. One demands clarity. The other demands a host.

This isn’t about money. It’s about soul. Do my children deserve a father obsessed, humiliated, gripped by a single grievance? I know what bitterness looks like. It looks like a man who dies alone. And no institution—not even a university rotted with cowardice—has the power to ruin my life. But bitterness does.

And here is the tragedy: you often don’t see it coming. Bitterness is a stench you get used to.

I once worked on a Roman-era dairy farm in France. One night, I stumbled into the pit where cattle waste was shoveled—no tractor, just me, a shovel, and a cart that may have been a gift from Caesar. Within seconds I was waist-deep in excrement. I pulled myself out, drenched to the ribs. By the time I made it back to the farmhouse, I no longer noticed the smell. But it was there. Everyone noticed. Bitterness is like that.

Bitterness is like cat piss on your best laundry. Our family’s geriatric cat, Masha, has developed a new philosophy: why use the litter box when there’s a fresh pile of Lululemon to soak? I left the bedroom door open, and she went full Jackson Pollock on my summer wardrobe.

Thanks to nasal polyps, I lack the basic evolutionary tool to detect this betrayal. To me, grey pants with dried cat urine look perfectly acceptable. I’d walk around in them, oblivious—until my daughter caught a whiff of the truth. That’s bitterness: invisible to you, but unmistakable to everyone else. And five cycles through the machine won’t wash it out.

I will not be bitter. I will not die like my blood father, alone and angry. I will live like my real father—my adopted father—a Christian man who had every excuse to be bitter after a childhood in Depression-era poverty. But he wasn’t. He was decent. Kind. Unbroken.

A few months ago, my wife, my son, and I went to hear a Holocaust survivor speak. Elly Gotz. His life was scorched by history, but he radiated something rare: clarity without bitterness. Elly didn’t have to spell it out, he showed it.

Elly taught me a lot, but, he like my daughter and the cat piss, showed me what I was blind to. I’m not sure Elly would like being lumped in with a cat piss analogy,

Actually I bet he’d find it hilarous.