The Equal Misery of Equity

Where Neurologists Earn Like Waiters and the Drunks Still Get Hired

If you believe in free speech, subscribe to support uncensored, fearless writing. The more readers who chip in, the more time I can devote to it. I’m not yelling from the sidelines—I’m a university professor fired for criticizing Hamas.

Subscribers get at least three essays a week, plus open comments. It’s $6/month (less than $4 USD). People say, “It’s just a cup of coffee,”—so when you’re at the Substack café, pick mine. Cheers.

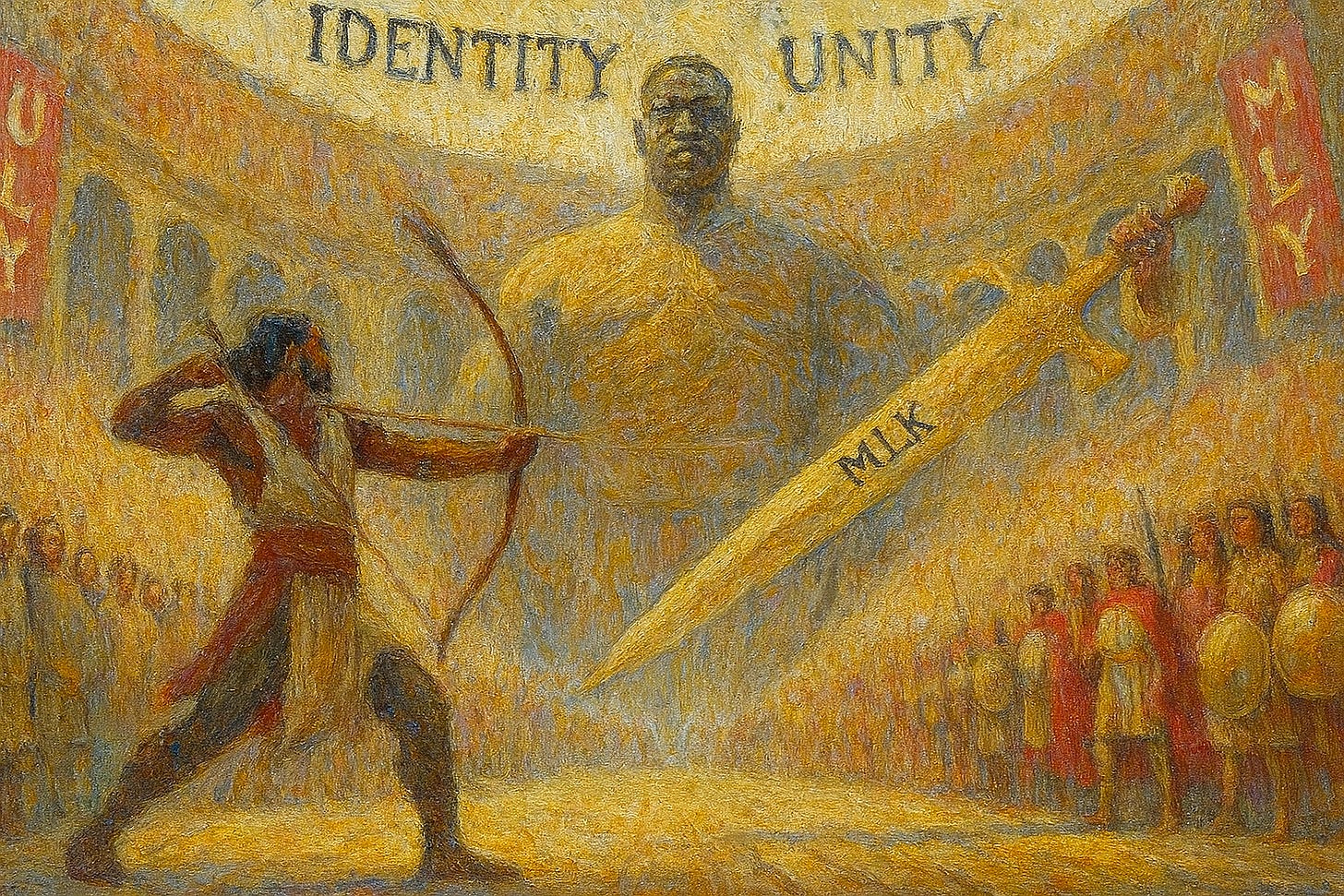

The quality of opportunity and identity politics—two eternal pugilists in the intellectual arena, one armed with reason, the other with a grievance pamphlet and a bullhorn.

On the one hand, you have a principle that, in theory, gives each person a fair chance to run the race—regardless of whether they arrive in Prada or in Payless.

On the other, you have identity politics, which mutates that same race into a chaotic scream-fest of competing victimhoods, where the winner isn’t the swiftest but the most aggrieved.

Equality of opportunity is widely misunderstood; it merely insists the state cease rigging the game. It does not promise that all players start with identical skills, talents, or fortune, nor does it deny that life’s dice roll differently for each. It does not render the world fair—only less arbitrarily cruel.

John Locke, bless him, built the philosophical bones of this idea in his Second Treatise of Government. His brand of equality—rooted in natural rights—preached that all are born with life, liberty, and property. The Americans, ever fond of euphemism, swapped that last one for “the pursuit of happiness,” as if Jefferson had read a Hallmark card and mistaken it for moral clarity.

But Locke’s real revolution was to decouple success from lineage and tether it instead to liberty. A man might be poor or unlucky, but he could strive. Government’s job was to stay the hell out of the way.

Contrast this with identity politics, that petulant religion of the discontented, which holds that individuals are but mouthpieces for their category—racial, sexual, gendered, or invented yesterday in a sociology department. If equality of opportunity tells you to lace your boots and run, identity politics demands a bureaucrat adjust the terrain based on your skin tone, genitals, or intersectional horoscope.

This ideological project doesn’t just divide—it actively insists on division. As Malcolm X acidly observed, “The white liberal differs from the white conservative only in one way: the liberal is more deceitful.”

And what could be more deceitful than a movement that claims to champion empowerment by reducing people to demographic widgets?

Orwell, that grim prophet of totalitarian rot, spoke of “smelly little orthodoxies”—those decayed ideologies clung to out of comfort or cowardice. Today’s orthodoxies smell worse than ever. They don’t just rot from lack of scrutiny; they scream when you try.

Language has become the first casualty. Colonialism, whiteness, climate justice, cultural appropriation—all now mean what the shrillest activist says they mean. Disagreement isn’t met with argument but with accusation. And thus, as Orwell foresaw, the degradation of language becomes the degradation of thought.

Where equality of opportunity says, “Let all try,” identity politics hisses, “Let us define who may try, and how much assistance we shall mandate.”

As Milton Friedman once warned, “A society that puts equality—in the sense of equality of outcome—ahead of freedom will end up with neither equality nor freedom.”

What he meant, of course, is that envy, once it gets its trembling hands on the levers of state power, doesn’t lift the masses—it simply brings everyone down to the same numbing, flattening mediocrity. Equality of misery, not opportunity.

Permit me a brief anecdote from the utopia of enforced fairness: my wife, a trained neurologist in post-Soviet Russia, earned the same monthly pittance as a local waiter—four hundred dollars. The bureaucratic logic? Why reward skill when you can sanctify sameness. After all, it’s much easier to regulate envy than excellence.

Now, consider the real-world implications. A few of her colleagues—fellow physicians, mind you—would stroll into the hospital visibly pickled. Why wouldn’t they? Their salaries were an insult to their education, and if by chance they were fired for malpractice, the worst that could happen was they’d pour coffee for a living, with roughly the same pay and considerably less paperwork. Call it the Communist Starbucks Career Path™.

This is not equity. This is egalitarian rot. The levelling impulse, when weaponized by state machinery and wrapped in the stale moralism of envy, doesn’t create justice. It creates a culture in which competence is punished, ambition is pathologized, and vodka is the only remaining incentive.

Equality of opportunity respects merit, autonomy, and ambition. It accepts that some will fail, and others will rise—not always fairly, but at least freely.

Identity politics, on the other hand, creates a sort of bureaucratic Paralympics in which the field is endlessly adjusted to satisfy the sensitivities of the latest grievance cohort. Human rights tribunals become ideological enforcement committees, where evidence is optional, presumption of innocence is heresy, and the clerks behave like Maoist interns with a DEI certificate.

Merit is not just devalued—it’s treated as a kind of white supremacy. If a member of a designated group stumbles, the entire field is regraded, not to help them walk, but to shame those who can already run.

This new catechism thrives on division. Intersectionality—the faith’s more deranged cousin—insists that identity is a stackable oppression poker hand, and the more chips you claim, the more virtuous you become.

As for the phrase “systemic racism,” it has become a kind of secular incantation. To question it is to invite denunciation. Its definition is elastic enough to mean anything from Jim Crow to awkward pauses in meetings. Try inquiring whether every disparity is a sign of discrimination and you’ll be told to shut up and check your privilege.

Identity politics disciples behave like Calvinists of the progressive left: their station is foreordained by history, their enemies are tainted by original sin, and any dissent is a form of heresy.

But let’s return to King—Martin Luther, not Stephen. His “I Have a Dream” speech is now quoted so selectively it may as well be rebranded as “I Have a Footnote.”

King’s aspiration, that his children be judged by “the content of their character,” has aged badly in the Church of Identity, where character is irrelevant and identity is destiny. To suggest otherwise is to be branded a traitor—or worse, a moderate.

And yet, King wasn’t vague. He also warned: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” But he was speaking of injustice in the legal and civic sense—not perceived slights, not jokes, not awkward stares in lecture halls.

Malcolm X, by contrast, was no wide-eyed integrationist. “If you’re not ready to die for it, put the word ‘freedom’ out of your vocabulary,” he growled. But even Malcolm, in his later years, began softening toward the idea that people were more than their category, that common cause could be made across the aisle of race.

Were either alive today, both men would be run out of the room. King would be sneered at as a respectability politician. Malcolm would be accused of black male privilege and cis-heteropatriarchal complicity.

We now inhabit a world where cooperation across group lines is suspect, where the goalposts of justice move according to the latest hashtag, and where victimhood is an industry with tenured posts.

The result? A new hierarchy, just as cruel and far more self-righteous than the old one. Grievance is now coin. Identity is now armor. Victimhood is now virtue.

And with this shift, we trade the liberal dream of shared humanity for the bureaucratic nightmare of managed group resentment.

So yes—equality of opportunity and identity politics are at war. One asks, “What can you do?” The other insists, “What was done to you?”

And in that difference lies the fate of our civilization.

If you found value in this article and wish to support my ongoing work please consider leaving a tip. Your support helps me continue producing uncensored content on critical issues.

Thanks for these insights, Paul, and your ever-increasing wisdom. Cute dogs, by the way! You pick good quotes to share with us, and I enjoy your AI-created artwork. My grown children had warned me about the issues you describe in the first part of your article, way back before October 7th. I now stand corrected, and have ‘updated’ some of my left-leaning perceptions. You avoided mentioning your own situation in this one, which was a good call. Your support for Israel and the Jewish community are hugely appreciated. Go from strength to strength!