The Defecating Canadian: Irish Roots, Wigs, and an Aloe Apocalypse

As a shitty bonus, cancer's long killing march through my family.

If you believe in the importance of free speech, subscribe to support uncensored, fearless writing—the more people who pay, the more time I can devote to this. Free speech matters. I am a university professor who was suspended for criticising Hamas - so I am not speaking from the bleachers.

Please subscribe to receive at least three pieces /essays per week with open comments. It’s $6 per month, less than USD 4. Everyone says, "Hey, it’s just a cup of coffee," but please choose my coffee when you come to the Substack counter. Cheers.

Generally, diarrhoea is not a good conversation starter.

But it features in my trip to County Donegal and the village of Kerrykeel, where I discovered Irish roots, met distant relatives, and chased the romantic dream I’d called Ireland. The itch began earlier, with stories from my grandmother — how our family had tired of being crapped on by the English. In 1904, half said “enough” and sailed for Canada.

At 19, I worked on a farm near Strasbourg. My labours mostly involved crisscrossing the French countryside, dropping off bags of milk and ensuring the fly-infested ones were redirected for home consumption. Character-building, if not exactly cinematic.

Life in Winnipeg wasn’t going well, so I escaped to Europe for a volunteer year. I’d started university at 17 — woefully unprepared — in a brutal pre-vet program that chewed me up and spat me out.

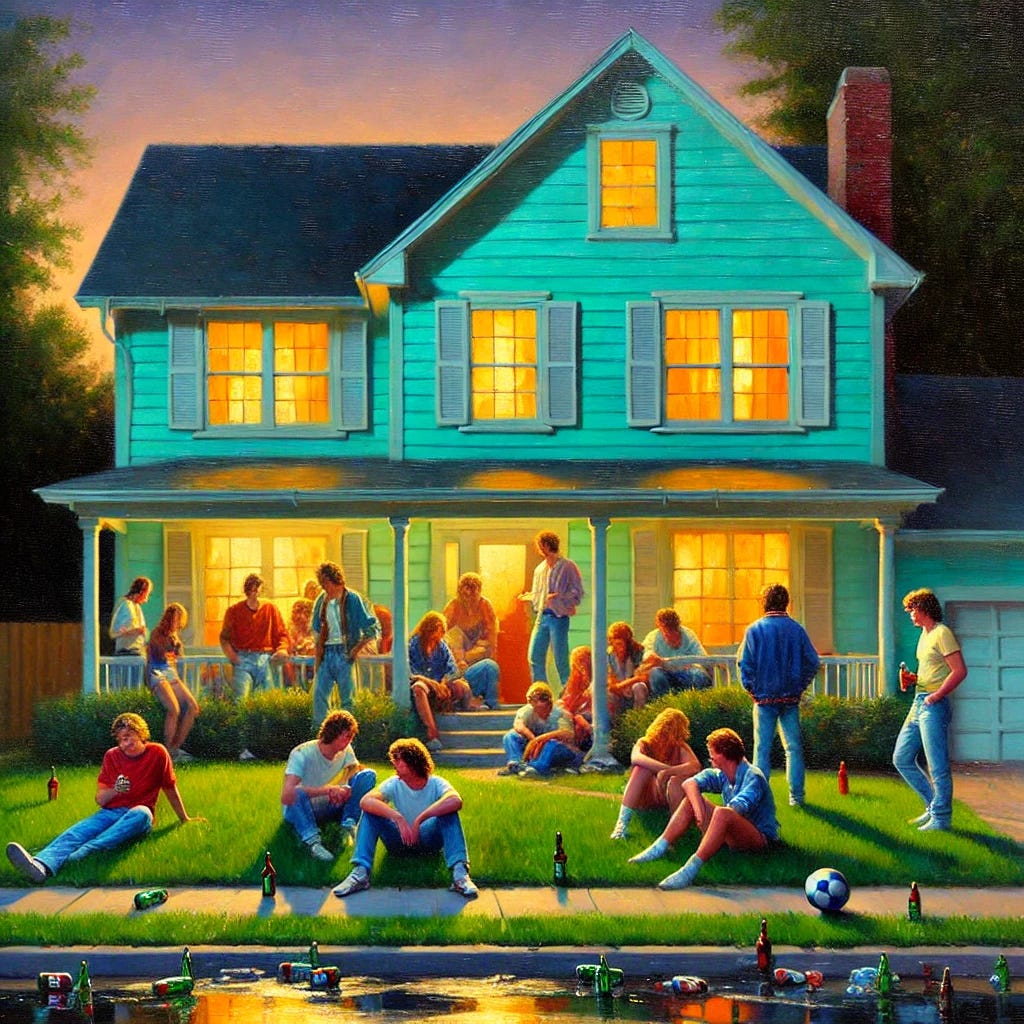

Home life in our turquoise two-story in Fort Garry was chaoic. My sister had long left. My brother and I were often on our own, dad was taking care of mum.

Mum had been diagnosed with terminal cancer when I was 15. She was in and out of the hospital, her impending death hanging over the household, bringing with it a pervasive melancholy that I could not drive out.

Mum distracted herself buying wigs, chemo having claimed her hair.

I remember sitting in Mr. Albertson’s chemistry class after my parents delivered the news. It wasn’t the day to light Bunsen burners or laugh at Mr. Albertson’s casual racism toward the two Chinese exchange students in the front row. It was 1980.

Mum was going to die. There would be no parents, plural. My dad wasn’t the remarrying type. My shoulders dropped. No more tomato soup lunches in the tiny kitchen with Misty, our Westie, tapping at my leg for a cracker. The weight of anticipatory grief hunched me forward; I feigned a lash in my eye.

We were told she could last years. There remained a small, hopeful seat in the corner. Mum didn’t seem down about it.

They weren’t exactly forthright. Years later, as my brother Doug and I waited outside her palliative ward, a nurse leaned in, breathlessly optimistic: “She might live six more months,” like she’d just told us we had enough gas to get to Emerson and back without stopping at the Domo.

Memory doesn’t play like a recorder. It comes in flashes—smells, fragments, sudden intrusions.

We built life around Mum’s chemo schedule. After each treatment, she and Dad would retreat to our farm near Vulcan, Alberta. My brother and I would fill the house with our friends — mostly boys.

Drinking was a dedicated enterprise. We calculated alcohol by cost-per-drunkenness. Cooking sherry or 7% Club beer were preferred, even though they were wretched. Drunkenness wasn’t a byproduct; it was the goal.

Our neighbours — God help them — would peek out at 1 a.m. to see us playing a game called “Pee Ball,” which, as the name suggests, involved urinating on the ball. Apparently, I played it.

In those days, neighbours didn’t call the cops. They just sighed and waited for us to grow up.

Mum stayed optimistic. There was always talk of “fighting,” but no, the cells were not intimidated by a positive attitude. You don’t fight cancer. You comply. You endure. She did it all: radiation, chemo, hormone therapy.

Dad, for his part, slept beside her on a thin blue yoga mat on the tile floor. Not a man of tears or declarations, he fought with his presence. It was like watching a small boy take wild swings at a Goliath — futile but ferociously loyal.

By then it was 1986 — nearly 40 years ago — and we staggered down that hallway, punch-drunk on early grief. We hoped for miracle cures, yet we knew better. We collapsed into chairs beneath a window overlooking the St. Boniface parking lot. I remember the yellowed tiles, and the urge to run.