How “Human Rights” and "Human Rights Offices” became Weaponised by the Unjust and Cruel

We should not determine whether justice exists by the language in an office holder's title. Such is foolishness.

Human Rights laws were conceived as restraints on power, not as instruments for its discretionary use. They emerged from catastrophe—war, genocide, ethnic cleansing—and were grounded in a sober recognition that authority, when left unchecked, will abuse itself. Their moral legitimacy rested on objectivity: evidence, notice, proportionality, and the presumption of innocence. Remove those foundations, and “human rights” ceases to be law. It becomes ritualised coercion.

Across much of North America, that transformation is no longer theoretical. It is already well advanced.

What now operates under the banner of human-rights enforcement—particularly within universities, colleges, corporations, and administrative tribunals—often bears only a cosmetic resemblance to justice. These regimes do not function as legal systems in any meaningful sense. They do not reliably follow statute, adhere to their own codes, or respect the basic architecture of natural justice Instead, they operate through an extraordinary degree of subjectivity, administered with caprice, moral fashion, and institutional self-interest.

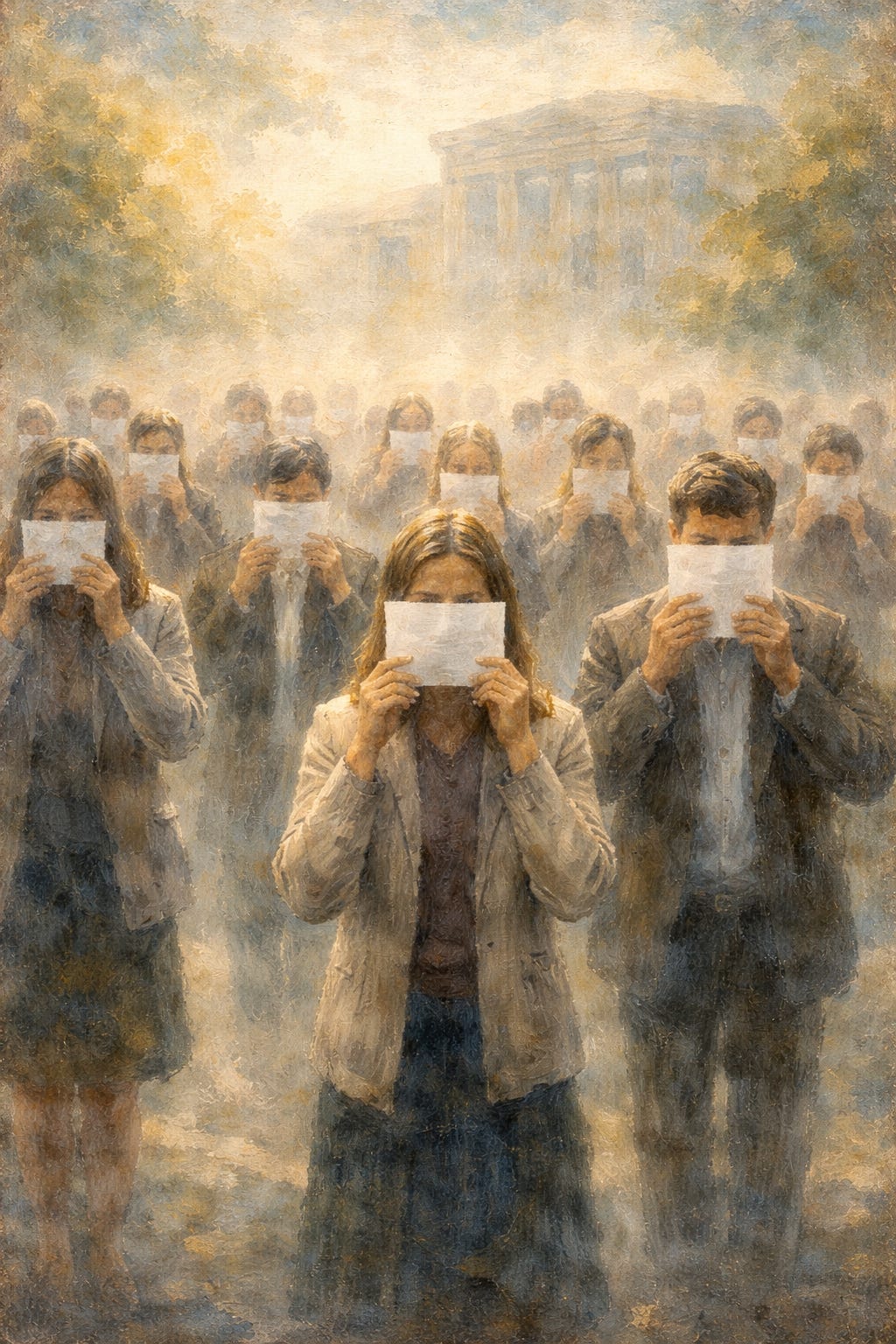

This subjectivity is not a flaw; it is the mechanism. The purpose is not adjudication but intimidation. Arbitrary punishment is not an accident of the system—it is a feature, and a subordinate one at that. The primary function is to induce self-censorship. The uncertainty, the inconsistency, and the absence of clear standards are precisely what make the system effective. When no one knows where the line is, everyone learns to stay well back from it.

Human-rights departments thus function as beacons of repression. They do not need to punish everyone. They need only punish someone, periodically, conspicuously, and without shame. The chosen individual becomes an example. The message is transmitted efficiently and wordlessly: this is what happens if you speak out of turn.

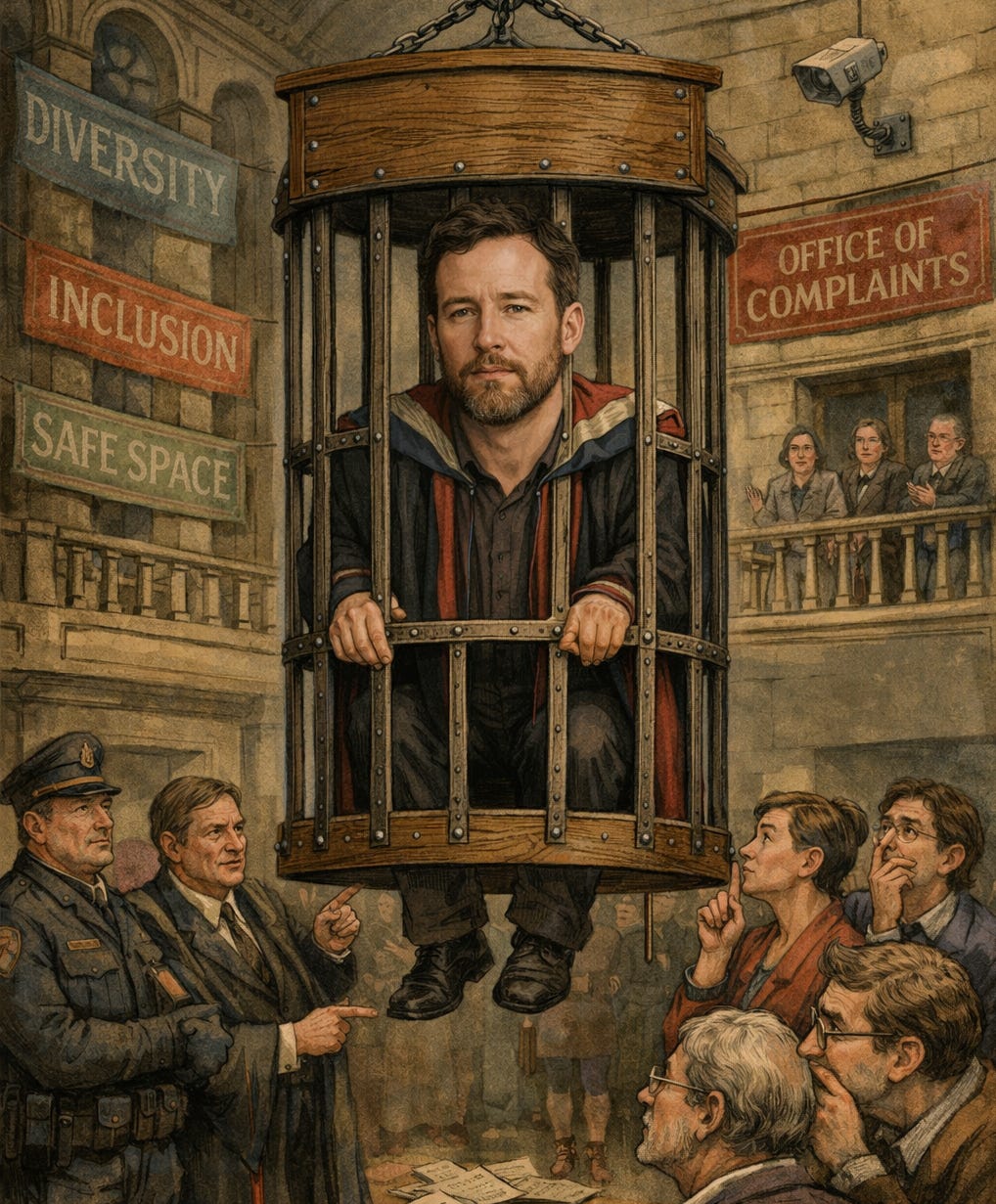

The analogy is medieval because the logic is medieval. In earlier centuries, the bodies of executed criminals were displayed in gibbets at crossroads—not primarily to punish the dead, but to instruct the living. Modern bureaucracies have perfected a bloodless version of the same ritual. Careers are destroyed, reputations annihilated, livelihoods erased, all under the antiseptic language of “process” and “safeguarding.” The spectacle is the point.

In this sense, contemporary human-rights offices have remarkably little to do with human rights. They exist to police speech, to intimidate dissenters, and to enforce ideological conformity on behalf of institutional power. Law is incidental. Fairness is optional. Fear, however, is essential.

And fear works.

The reflexive response to this critique is as predictable as it is dishonest: so you support racism, then? So you are Islamophobic? Or the most infantile?: So you hate human rights?

This is not an argument; it is childish moral intimidation. Racism, harassment, incitement to violence, and criminal intimidation are already unlawful. They are addressed through criminal law, civil remedies, and workplace safety statutes. None of these requires anonymous accusers, secret evidence, or tribunals that operate without adversarial testing. The question is not whether discrimination should be confronted, but whether it should be confronted without law.

Human-rights bureaucracies flourish precisely because they dispense with those constraints.

Consider the proliferation of bias-reporting systems on university campuses. At Indiana University, students were encouraged to report speech they found “demeaning” or “harmful,” even when it fell well short of harassment or threat. The resulting administrative scrutiny—often without disciplinary safeguards—was widely criticised for chilling speech at the heart of academic inquiry.

When the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear a challenge to the policy in 2025, dissenting voices warned that the university had effectively authorised the policing of unpopular ideas under the guise of community care.¹

Title IX adjudications (de facto US human rights) provide an even clearer illustration. Across the United States, courts have repeatedly overturned university decisions that denied respondents basic procedural protections: access to evidence, the right to cross-examine, and the right to impartial adjudicators. In many cases, students were eventually cleared—but only after their education, finances, and reputations were irreparably damaged. The process itself became the punishment.

Canada does not share the United States’ commitment to free speech, and our civil justice system is far more inclined to protect institutions than individuals. This is not a secret; it is a design choice, defended in the soothing language of “balance,” “harm,” and “social cohesion.”

And yet—somehow—we remain convinced of our moral superiority.

There is a saying that if you repeat a claim thirty times, people will begin to accept it as the truth. In Canada, we cleared that threshold years ago. We recite our virtue reflexively, as a national mantra, even as we narrow the space for dissent, outsource judgment to bureaucracies, and congratulate ourselves for being gentler than our neighbours while becoming less free.

At the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, thousands of complaints are dismissed annually, not on their merits but on procedural thresholds, often after years of delay. The Supreme Court of Canada has acknowledged that human-rights processes can inflict serious psychological harm even when no violation is ultimately found.² Yet the machinery persists, largely unaccountable, insulated by moral rhetoric and administrative deference.

Academic institutions reveal the pattern most starkly. At Evergreen State College, biology professor Bret Weinstein objected to a campus event encouraging white students and faculty to absent themselves for a day.

His dissent—nonviolent, reasoned, and principled—was treated as intolerable. Student complaints escalated into administrative action, police presence followed, and Weinstein was effectively forced out. No finding of misconduct was required; ideological nonconformity was sufficient.

At the University of Pennsylvania, law professor Amy Wax endured years of investigation for statements deemed to create a “harmful environment.” Her views were controversial, but the institutional response illustrated how discomfort could be elevated into a disciplinary category.

In Canada, the University of Ottawa suspended a professor for quoting a racial slur in an academic context—only to reverse course after national outcry. The incident demonstrated how readily human rights logic can be invoked against speech absent any threat or intent.

These examples establish a pattern: once speech is perceived as harmful, the process becomes optional.

It is within this landscape that the Finlayson case must be understood. Reported by Juno News, John Ivison at the National Post, and examined by the Canadian Antisemitism Education Foundation (CAEF) and Honest Reporting Canada, the case involved Paul Finlayson, a business instructor at the University of Guelph-Humber.

In October 2023, Finlayson posted on social media that he supported Israel and likened Hamas to Nazis—a political and moral condemnation of a terrorist organisation following the October 7 attacks. The speech occurred off campus and was not directed at any member of the institution.³

What followed was not adjudication but escalation. Finlayson was suspended without charges, subjected to severe restrictions on communication, and ultimately terminated. No formal hearing occurred. No meaningful particulars were ever provided. The evidentiary material itself was later acknowledged to be unavailable, altered, or missing. What replaced law was a mad, multi-layered jumble of procedural improvisation—something closer to chaos theory than due process—an ad hoc structure held together by binder twine, duct tape, and institutional nerve.

It was so unstable that a mild breeze of scrutiny could have brought it down. If the consequences had not been so devastating, the arrangement would have been comical.

The human-rights complaint at the centre of the matter was procedurally defective from the outset: the claimant lacked standing; the so-called “investigation report” was a bespoke smear drafted by a handsomely paid hired gun selected by the Human Rights Office itself; and the claimant was the Vice-Provost—effectively accuser, architect, and beneficiary of the process.

We are invited to believe otherwise only because institutional counsel later issued a comically formal letter assuring readers that the Vice-Provost would “not be involved,” notwithstanding the small detail that her direct subordinate ultimately signed the termination letter.

To complete the farce, the professor whose allegations triggered the complaint was a long-time acquaintance of the Vice-Provost. Yet despite this carnival of conflicts and irregularities, the sanctions imposed were maximal.⁴

The unions were no counterweight to this collapse. OPSEU Local 562 did nothing to defend Finlayson and formally dropped him three months before his termination, effectively ratifying the process through silence.

That abdication sits uneasily beside the fact that dozens of Jewish union members in Ontario have since turned to the Human Rights Tribunal themselves, alleging that their own unions—including OPSEU and CUPE—have fostered environments that are hostile, discriminatory, and indifferent to antisemitism. The pattern is unmistakable: where institutional and ideological alignment exists, scrutiny evaporates; where it does not, procedure hardens into punishment.

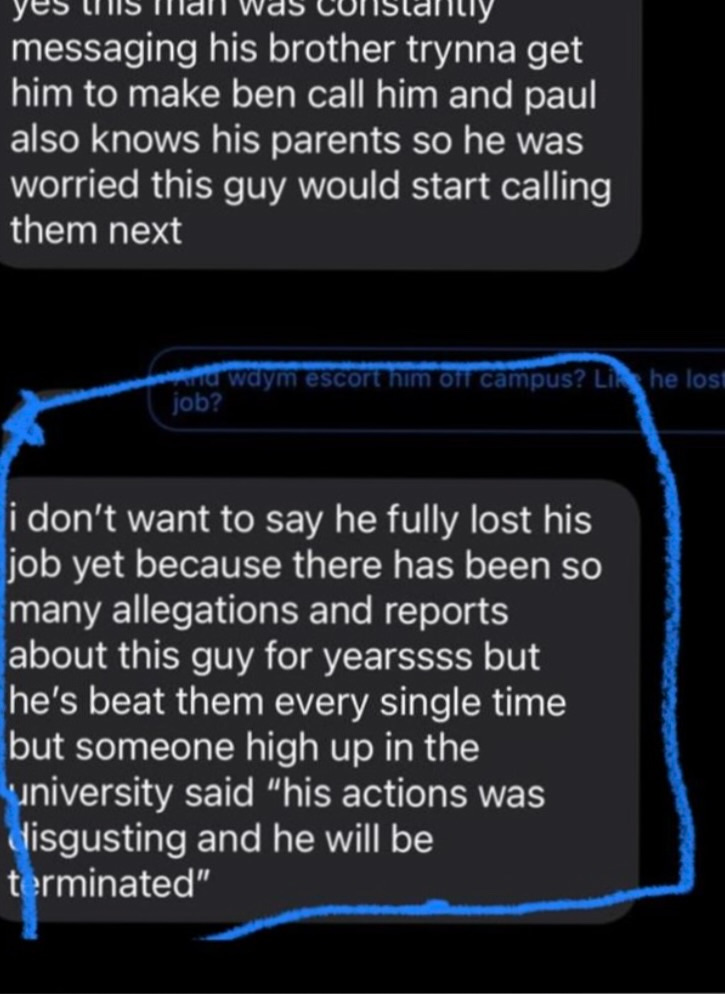

Alongside the formal process, a documented reputational campaign against Finlayson unfolded almost immediately. Within hours of the suspension—and weeks before any charges were articulated—members of management, faculty, and staff reportedly began communicating with students about Finlayson’s absence.

According to accounts placed on the public record, students were told by staff and faculty not that he had been removed pending review of political expression, but that he was absent due to a five -year record of alleged violence and sexual misconduct, including claims that he had been arrested, handcuffed and led away for such crimes.

(Fig 1: See defamatory staff text - or communicated verbally - sent to students within hours of Finlayson being suspended without charges. Note that on day one, weeks before charges are produced, an anonymous determination by senior administration is made that Finlayson will be fired.)

These assertions were false and contained no truth. Finlayson’s teaching, writing and academic record were stellar; he was considered the teaching star of the Business Department. But when he said he stood with Israel, this was forgotten.

There were no such charges, arrests, or allegations in any police or judicial forum. The University of Guelph Humber management refused to stop the defamation, and the Humber Public Safety Manager threatened Finlayson with criminal charges when he asked staff to stop defaming him.