Free Alberta

On what happens when a mortgage-paying province is treated like a freeloader — and why the threat of departure may be the only language Ottawa still understands.

“Nothing improves the manners of a complacent capital faster than the faint possibility that someone might walk away.”

Federations rarely collapse in drama. They erode. One partner keeps giving while the other keeps governing, and eventually the giver asks a question that polite countries prefer not to hear: what exactly binds us together — habit, respect, or simply the absence of consequences?

Canada prides itself on unity, but unity does not sustain itself through slogans. It survives when each region believes it matters. It weakens when one region suspects it exists mainly to fund decisions made elsewhere.

What now stirs in Alberta does not resemble a tantrum. It resembles recognition. A province has begun to notice that the bargain feels less like a partnership and more like a managed obligation. Regions do not threaten to leave when they feel heard; they threaten to leave when they conclude that loyalty has turned them into furniture.

Start with arithmetic, because numbers refuse to flatter anyone.

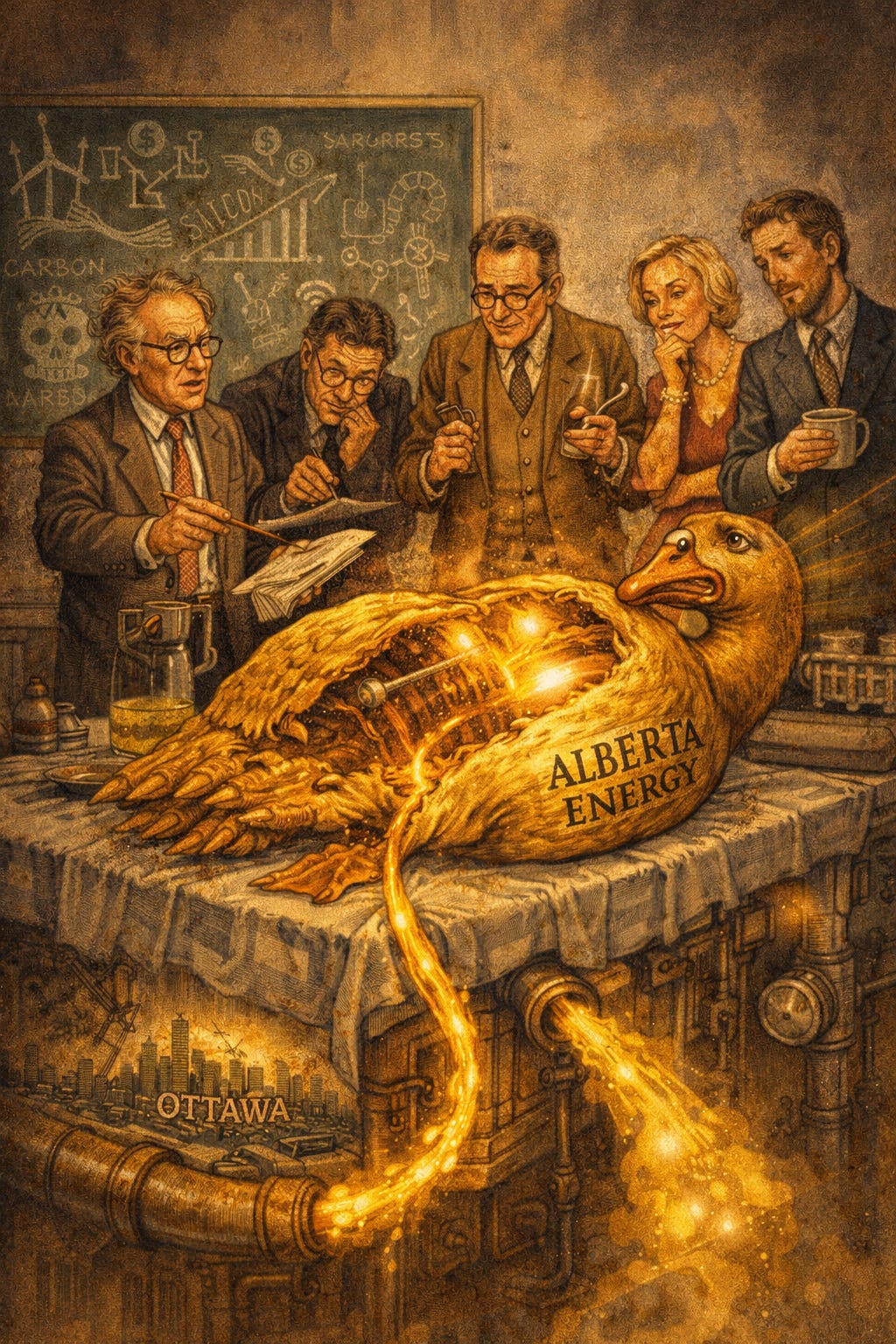

Canada sells energy to the world on a massive scale. Oil and natural gas account for roughly a third of the country’s goods exports. Alberta produces the overwhelming share of that oil and a dominant portion of the gas. Remove Alberta’s energy sector, and Canada would not merely lose revenue — it would have to rethink its economic identity.

Call the industry what it is: the golden goose.

Yet watch how the country often speaks about it. Commentators wrinkle their noses. Editorialists moralise. I have read Eastern writers describe oil workers in terms that would end careers if applied to almost any other labour force — insinuations about violence, coarse behaviour, social backwardness. The subtext rarely hides: those who design apps and wear suits belong to the future; those who extract resources belong to the past.

Strip away the manners, and the message reads plainly — not like us.

It insults the people who build the wealth. It betrays a striking ignorance about what finances the national comfort. A country that depends on resource exports ought to understand the difference between criticising an industry and sneering at the citizens who sustain it.

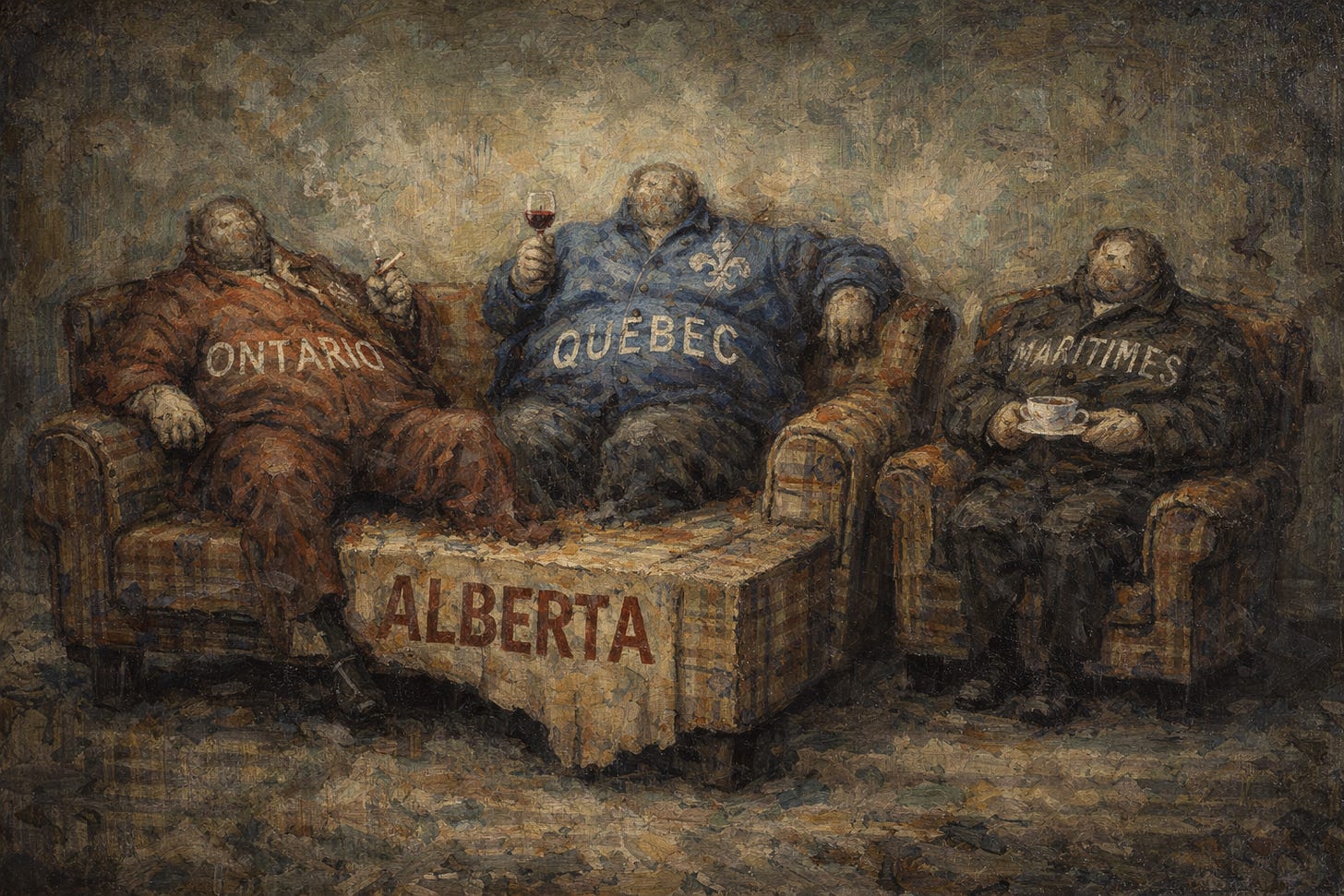

For years, the Fraser Institute has tried to measure this imbalance. Its estimates place Alberta’s net contribution to federal finances at roughly $244 billion between 2007 and 2022 — federal taxes paid that exceeded federal spending returned to the province. Economists can quarrel over models until the sun burns out, but the central fact stands firm: Alberta sends more to Ottawa than it receives.

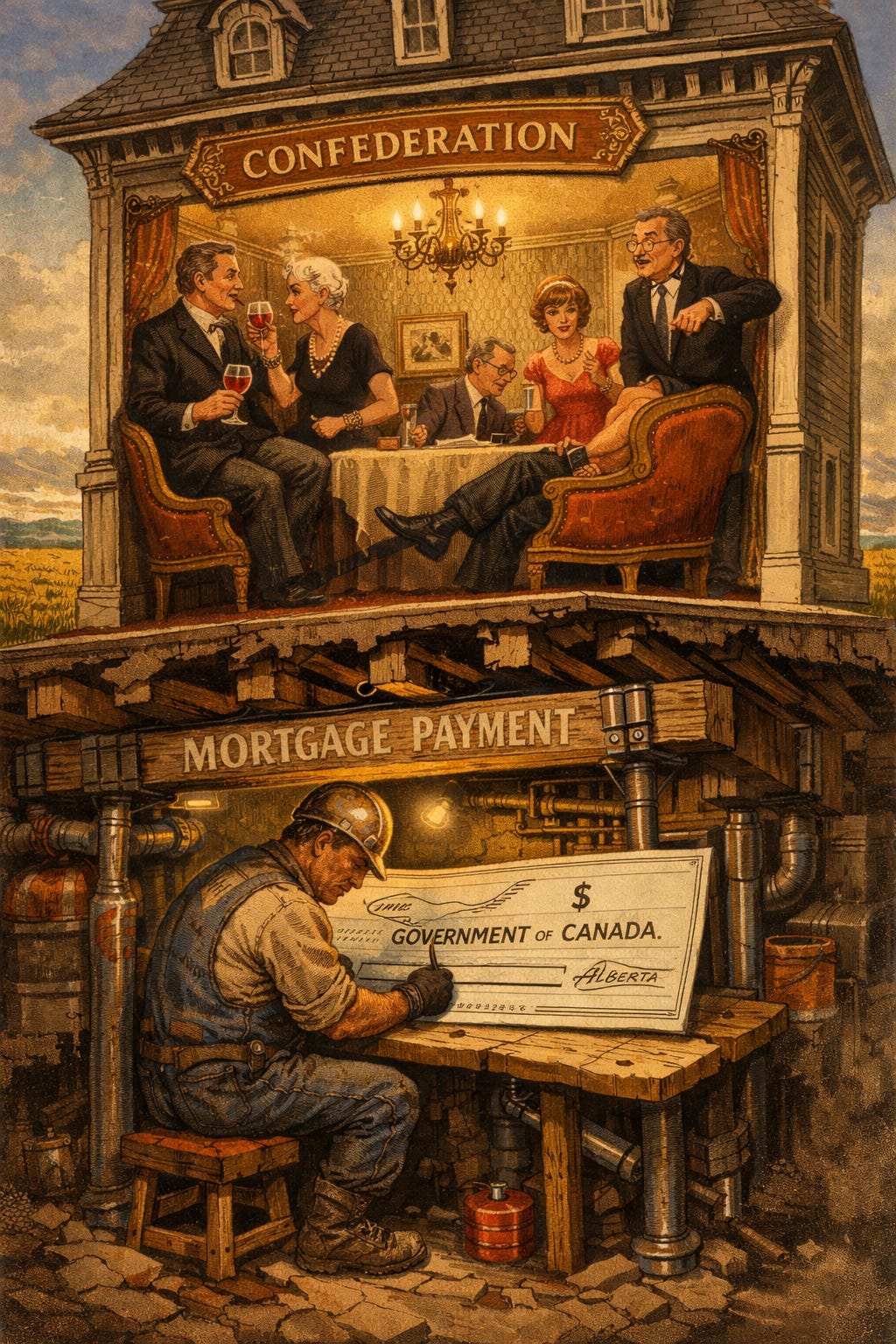

Picture a household. One member pays much of the mortgage — yet the rest of the family speaks about him as though he contributes little. He eats too much, talks too loudly, and embarrasses guests. Gratitude never enters the conversation.

Alberta has become that teenager in the basement — except the teenager pays the bills.

No political structure survives long when it mixes financial dependence with cultural contempt. Redistribution may form part of nationhood, but redistribution without respect turns cooperation into extraction.

The deeper issue lies not in fiscal transfers. It lies in tone.

Watch the national reaction whenever Alberta raises a complaint. Commentators do not lean in; they dismiss it. Farmers become rubes. Energy workers become relics.

The province itself becomes shorthand for stubbornness.

Then observe the country when Quebec declares sovereignty. The atmosphere changes at once. Analysts parse the history. Politicians lower their voices. Journalists search for nuance. Canada does not scold Quebec; it studies Quebec.

Alberta receives lectures.

The contrast reveals more than any policy paper. Separatism in Canada does not elicit a single response; it elicits two. Quebec raises constitutional questions. Alberta raises eyebrows.

Subsequently, the media expresses shock as alienation spreads.

Nothing drives political estrangement faster than dismissal. Tell people long enough that their grievances lack legitimacy, and they will stop asking for permission to feel them.

In fact, much of the current commentary — invoking treason, portraying separatist sentiment as vaguely uncivilised — strengthens the very movement it seeks to shame. Those who believe they defend national unity often erode it, line by line, headline by headline.

The obvious question follows: would independence enrich Albertans?

Answer it honestly or not at all. Independence would not rain cheques from the sky. Sovereignty transfers burdens as well as authority. Alberta would assume responsibilities now carried by Ottawa — defence contributions, border systems, foreign service, regulators, and its share of the national debt.

But remove the persistent net fiscal outflow, and Alberta would inherit something governments prize above almost everything else: room to manoeuvre.

The province already operates without a provincial sales tax — a stance so embedded that any independent government would struggle to reverse it. The federal GST could remain, shrink, or morph into something local. Income taxes would stay; modern states run on revenue. Yet the absence of a large transfer raises the possibility of lower effective taxes or stronger services per dollar.

Not paradise. Not ruin. Control.

Pensions provoke predictable anxiety, yet Alberta has already studied the mechanics of a standalone plan, arguing that its younger workforce could support long-term stability. Critics dispute asset shares; such disputes accompany every institutional divorce. Feasibility no longer belongs to the realm of fantasy.

Employment would hinge on confidence. Markets do not faint at the sight of new borders; they faint at chaos. Keep trade flowing, signal regulatory stability, and capital tends to behave rationally. Oil does not stop moving because a constitution changes punctuation.

Risk would enter through uncertainty — particularly if Ottawa chose hostility over pragmatism. A punitive negotiation could slow investment and rattle markets.

But Canada would bleed too. Alberta does not occupy a decorative corner of the economy; it anchors it. Sabotaging that engine would resemble burning down a duplex because one dislikes the neighbour.

Geography would then hand British Columbia unexpected leverage. Alberta lacks tidewater; ports matter. Cooperation would enrich both provinces. Obstruction would stunt both. Economic gravity rewards partnership far more reliably than theatre.

For the rest of Canada, Alberta’s departure would force a reckoning. Lose a major fiscal engine, and the federation must redraw its financial map. Redistribution debates would sharpen. Political weight would drift further east. The country would shrink economically even as it tried to project steadiness.

As far as economic outcomes? It would depend on assumptions about how the Rest of Canada (ROC) would treat Alberta and whether it forms a partnership with the US. Lots of questions, the future can’t be assured, but one thing is clear: the ROC would be poorer.

If Alberta were to depart Confederation, the fiscal consequences for the remainder of Canada would not be theatrical — but they would be immediate. The Fraser Institute estimates that Alberta contributes roughly $14 billion more annually to federal coffers than it receives in return, a surplus large enough that its disappearance would leave Ottawa with a choice familiar to all governments when arithmetic intrudes: raise taxes, cut spending, or borrow more and pretend the reckoning lies somewhere beyond the next election.

One modelling exercise suggests that replacing this lost revenue purely through consumption taxes would require lifting the federal GST from 5 percent to roughly 7 percent — an increase sufficient to cost the typical Canadian household in the neighbourhood of $1,000 to $2,000 per year, depending on income and spending patterns. No civilisation collapses over such sums, but neither are they trivial; electorates have been known to riot over far less than a quiet two-point tax rise.

For Alberta households, the ledger begins from the opposite side.

Albertans remit thousands more per capita to Ottawa than residents of most other provinces — a structural consequence of a younger work force, higher incomes and stronger employment. Adjust for the federal services a new state would need to assume, and serious estimates suggest that the average Alberta family could plausibly see its overall tax burden fall by somewhere in the range of $5,000 to $12,000 annually, assuming competent governance and no spectacular policy blunders.

The fact is that Alberta could, on its own, become a petro-state - perhaps one of the richest countries on the planet. But somehow Alberta is supposed to suck it up for Ottawa; they are supposed to be quiet while they have no meaningful voice in Canada, while they are demeaned by Laurentian elites and insulted by Quebecers and Maritimers who, ironically and shamelessly, are themselves incapable of paying their own bills, and have to rely on transfer payments from Western Canada to balance their provincial budgets.

But this is not an argument for separation; it is an argument for honesty.

Yet beneath all this arithmetic lies psychology — the force that often decides political futures.

Quebec grasped a simple truth decades ago: the credible possibility of departure commands attention. Whether one applauds the tactic is largely irrelevant; it works. Ottawa listens closely to provinces that might leave.

Alberta chose loyalty instead and discovered loyalty invites neglect when it appears permanent.

Perhaps Alberta has played the wrong game.

Do not mistake this for a call to dismantle the country tomorrow morning. Nations should not dissolve on impulse. But neither should they assume permanence grants them license to ignore a partner.

What fuels Western alienation is not merely cultural distance, pipeline disputes, or the familiar theatre of federal-provincial grievance. It is arithmetic — electoral arithmetic — and arithmetic, unlike rhetoric, has the irritating habit of being verifiable.

Canada is not represented strictly by population, and it never has been. Confederation was constructed as a federation of regions, not simply a census machine, and so the Constitution guarantees smaller provinces a minimum number of seats in the House of Commons regardless of demographic decline. Prince Edward Island, for example, possesses four seats despite having barely more residents than a mid-sized Calgary suburb.

The Atlantic provinces collectively retain representation that significantly exceeds what a pure population model would assign them.

This is not accidental; it is constitutional design. The so-called “senatorial clause” ensures that no province can have fewer Members of Parliament than it has senators. Add to this the “grandfather clause,” which prevents provinces from ever falling below historical seat counts, and one begins to see how political gravity tilts eastward even as population shifts west.

But the matter grows more delicate — and more revealing — when one turns to Quebec.

Quebec’s share of Canada’s population has steadily declined, from roughly 29 percent at Confederation to about 22 percent today. Under a strict representation-by-population formula, its relative seat share would fall accordingly.

Yet Parliament has repeatedly adjusted redistribution formulas to prevent any meaningful erosion of Quebec’s political weight. The province is now effectively guaranteed no fewer than 78 seats — a political floor written not by demography but by national anxiety.

One may understand the historical impulse: Quebec is central to the Canadian experiment, and successive governments have feared that a visible loss of influence might inflame separatist sentiment. However, understanding a decision does not preclude observing its consequences.

Those consequences are felt most sharply west of the Ontario-Manitoba border, where populations are growing faster, yet political leverage often appears weaker.

By the time federal election results reach the Prairies on a typical broadcast night, the outcome is frequently already apparent. Atlantic Canada reports first, followed by Quebec and Ontario — together accounting for the overwhelming majority of seats required to form government. The mathematical pathway to power rarely requires significant success in Alberta or Saskatchewan. Governments can, and often do, secure victory before a large portion of Western ballots have even been counted.

Perception matters in politics almost as much as reality, and the perception — fair or not — is that the West votes in an election whose conclusion has already been drafted elsewhere.

To point this out is not sedition. It is an observation.

Nor is the complaint that eastern Canadians vote incorrectly; democracy permits no such arrogance. The complaint is structural: when representation formulas systematically cushion some regions against demographic decline while others expand without commensurate influence, resentment becomes less a psychological quirk than a foreseeable outcome.

Critics often argue that Canada is a federation and that smaller provinces require protection to prevent their absorption by larger provinces. Quite so. But federations survive only so long as every partner believes the arrangement remains broadly reciprocal.

If rules are bent repeatedly in one direction — if formulas are revised to calm one region’s anxieties while another is told, with stoic Canadian politeness, to stop complaining — the federation begins to resemble not a partnership, but an inheritance dispute politely deferred.

And here we encounter the strangest rhetorical inversion of all: when Albertans raise these structural concerns, they are sometimes accused of disloyalty, as though noticing the architecture of power were itself an act of betrayal.

Yet mature countries do not demand silence from their provinces; they demand argument.

Indeed, one might suggest that the more troubling posture is not Western irritation but Eastern complacency — the assumption that the existing arrangement is not merely workable but morally settled, beyond serious reconsideration.

No federation should rely indefinitely on the patience of one region while adjusting its rules to reassure another.

None of this implies conspiracy; Ottawa is less a cabal than a machine responding to incentives. Political parties pursue the seats that deliver power. If electoral math rewards concentration in Central and Eastern Canada, strategy will follow arithmetic as surely as water follows gravity.

But incentives, once recognised, can be redesigned.

The deeper question, then, is not whether Canada has “stacked the deck” in some villainous sense, but whether its institutional safeguards — devised for a smaller, more eastern country — still reflect the demographic and economic realities of the twenty-first century.

Western provinces now drive a disproportionate share of economic growth, energy production, and export revenue. Populations rise, cities expand, fiscal contributions mount — yet many citizens feel their political leverage lags behind their economic weight.

Federations fracture not when disagreements emerge, but when one partner concludes that disagreement no longer matters.

And so the choice before Canada is not between unity and treason — a melodramatic binary unworthy of a serious country. The choice is between adaptation and drift.

A durable nation does not hush these conversations; it invites them. It does not accuse its dissatisfied regions of betrayal; it asks what conditions would renew their confidence in the common project.

For loyalty coerced is merely resentment deferred.

If Canada wishes to remain a partnership rather than a historical arrangement coasting on habit, it must confront these structural tensions with the same candour it once brought to the constitutional table.

Otherwise, the real danger is not that the West talks about alienation — but that, one day, it stops talking altogether.

If dangling separatism sharpens federal manners — as history strongly suggests — then the rational move may not involve packing bags but making it unmistakably clear that the bags exist.

I write this with no romantic illusions. Every province carries its own absurdities, Alberta included. But I recognise its grievance because the pattern has repeated for years: Ottawa displays an appetite for Alberta’s wealth while withholding curiosity about Alberta’s consent.

Even the national conversation hints at hierarchy. One still hears, without embarrassment, the notion that prime ministers ought naturally to come from Quebec, as though leadership flowed from geography rather than citizenship.

Treat a mortgage-paying partner like a nuisance long enough, and he will begin to price other houses.

So no, this is not a separatist manifesto. It is a reminder — admittedly delivered with a raised eyebrow — that federations endure through mutual regard, not moral instruction. Respect travels in both directions, or it stops travelling altogether.

If the faint possibility of departure restores balance, then perhaps the idea itself performs a public service.

Free Alberta — if only to remind this country that partnership means more than cashing the cheque.

Addendum

I was born in Winnipeg but raised in both Alberta and Manitoba. My grandfather homesteaded in Saskatchewan and later bought land in Alberta. I have lived and worked in Calgary, near Vulcan, AB and in Fort McMurray, places that do not theorise about Canada but build it.

I inherited a half-section of land in Southern Alberta that I sharecrop, and despite living in Ontario for thirty-five years, I still consider Alberta my home more than anywhere east of it. Roots do not relocate simply because a career does. My family and children keep me in Toronto - but I cheer for the Winnipeg Jets - and the Oilers when the Jets have run out of hope.

In 1928, my grandfather purchased what would become the home quarter section of family land near Ensign, AB.

On a hot August afternoon a few summers ago, we gathered near the house my father built. Nearby stood the old outhouse and the weathered red cook car with the green roof, relics from the era when threshing crews rolled across the land like seasonal armies, binding neighbours together in labour that was both punishing and communal. The shack remained as a quiet witness to a harder Canada, one less fluent in complaint and more practised in effort.

There, my twin brother, my sister, and I scattered my father’s ashes in the field. It felt less like a farewell than a return. The land had shaped my father, disciplined him, and, in the end, reclaimed him without ceremony.

The barley on the home quarter stood high and luminous, the beards lush and full. They swayed in the wind, like a chorus of stalks capturing the harmonies of an old gospel spiritual.

My heart, I know, will always remain on that land in Alberta — not out of sentimentality, but out of recognition. Some places do not merely host your life; they author it.

Today, I write from Ontario, but my instincts remain stubbornly Western.

My father and mother are buried in Alberta, and when my time comes, I hope they send me West as well — back to Vulcan — to rest under the same enormous sky.

And with that affection intact — and yes, with more than a little tongue in cheek — screw you Easterners who talk down to Alberta.

I’m not sure if I want Alberta to separate, but I am damn sure Alberta is the best province in Canada and should not be treated with such insufferable Laurentian disdain.

Free Alberta.

If you value this work, consider leaving a tip. It’s cheaper than therapy, less pious than public broadcasting, and the only censorship here is my bad taste. On second thought, it’s bad therapy.

Freedom to Offend is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This is unfortunately part of the reality and cost of keeping Canada together: “Even the national conversation hints at hierarchy. One still hears, without embarrassment, the notion that prime ministers ought naturally to come from Quebec, as though leadership flowed from geography rather than citizenship.”

Great article highlighting eqloquently what many of us realize about Alberta and its relationship to the rest of Canada. I am surprised that as many want to remain in confederation as poll results appear to indicate. But, who knows with the polls. I love Alberta, their spirit of independence, hard work, with just a slight edge of contrariness built into the freedom. I'd move there in a heartbeat if I was younger and not so tied financially to the east. But, if they separate in my time, I might still consider becoming a refugee....