Canada: The Diminishing Country

Not really. Thanks to Andrew Coyne on this.

If you give even half a damn about free speech, subscribe. It means I can continue doing this without needing to ask a gender-neutral AI for spare change. I’m a suspended university professor, not a pundit barking from the cheap seats. The link is below, click it before the lawyers take it away.

Please subscribe to get at least three uncensored, impolite, fire-in-the-belly essays per week. Open comments, $6/month. Less than \ USD 4. Everyone says, “That’s just a cup of coffee.” Okay, then buy mine.

The growth crisis deepens—again, as if we needed another reminder. Statistics Canada, whose job is to tell us how fast we’re circling the drain, has confirmed yet another decline in per capita GDP for Q4 of 2023. That makes five drops in the past six quarters—Canada’s worst sustained economic stumble in over 30 years.

But fret not! Most news coverage fixated on a microscopic 0.2% uptick in total GDP, and quickly hailed it as a masterstroke of economic resilience: “Canada dodges recession,” they declared. Yes, much like a drunk man dodging traffic by collapsing in the middle of the road. Our problem isn’t that the engine’s misfiring—it’s that we’re running out of fuel and pretending the car is fine because the hazard lights still blink.

This isn’t a cycle, it’s a coma. And we’re mistaking laboured breathing for progress.

What we’re experiencing is not a temporary softening but a chronic systemic decline. Canada’s so-called “potential” growth is now measured in centimetres. GDP per capita—the only kind that affects living standards—is not merely stagnant; it is declining. It’s in regression therapy. Adjusted for inflation, it’s below where it was in 2014. That’s nine years of economic activity with a net result best described as: “Oops.”

This secular decline didn’t come out of nowhere. It’s been creeping in like mould since the 1970s. Postwar Canada once experienced a robust 5% annual growth rate. By the 1980s, the rate had dropped to 3%. Then 2.4% in the 1990s. Down to 2% in the 2000s. Over the past decade? 1.7%. Last year: a majestic 1.1%. The only thing falling faster is our global reputation.

And crucially, our population is growing faster than our output. This means that, on average, each Canadian is becoming poorer. That’s not a “feeling.” That’s math. You remember math—our politicians certainly don’t.

And yet, Canadians persist in believing we’re among the richest nations on Earth. It’s a comforting delusion—like thinking maple syrup is a food group. Once, yes, we were top-tier. In 1981, we ranked 6th in per capita GDP among OECD countries. Today? 15th. We’ve been overtaken by countries we once pitied: Ireland, Sweden, Iceland, Germany, even Belgium. And if you’ve ever had Belgian customer service, you know how hard that is to forgive.

What’s more, this isn’t a fluke. It’s a forecast. According to the 2022 federal budget’s data (presumably filed in the drawer marked Oops), Canada is projected to have the slowest per capita GDP growth among all OECD countries through 2060. That’s not just losing; it’s pulling a hamstring on the way to the starting line.

Now observe the humiliation up close: In 1981, our per capita GDP was 92% of the U.S. Today, it’s 73%. Alberta, our allegedly rich province, would rank 14th among U.S. states. The bottom five provinces? Among the six poorest jurisdictions in North America. Ontario ranks just above Alabama. British Columbia is poorer than Kentucky. Let that sink in while you sip your sustainable oat latte.

And it gets better. Canadians work more hours than their OECD peers, but accomplish less. Productivity per hour? We rank 18th, and only Switzerland has posted slower productivity growth since 1981. Given how 2023 played out, we’ve likely been booted from the top 20 by now. This is the economic equivalent of being lapped in a one-person race.

Once upon a time, our productivity growth closely tracked that of the U.S. reasonably well. But since 2000, American productivity has grown three times faster. While we were debating whether “infrastructure” included yoga studios, they were building something.

And what does it all mean? Beyond fewer lattes and more roommates in your 40s, it means despair. Because when a society ceases to grow, it doesn’t just lose money—it loses hope. That lubricating fiction that tomorrow will be better than today evaporates. What replaces it is resentment—between the classes, the generations, and in Canada’s case, between the regions that all secretly hate each other anyway.

Still, some might protest: “It’s a long-term issue. Not urgent.” Yes, and heart disease is also slow-moving—until it isn’t.

The arithmetic is merciless. By 2040, a quarter of Canadians will be over 65, up from 19% today. In the 1970s, it was just 8%. And the over-85 crowd? Tripled since 1971. Will double again in 20 years. We’re not ageing gracefully—we’re ageing expensively.

What does this mean? First, costs. Healthcare costs double every decade after 55. Throw in pensions, elderly benefits, and you’ve got a demographic time bomb with a $3.9 trillion fuse (according to the C.D. Howe Institute). Add $1.2 trillion in CPP liabilities. Add federal net debt: $1.2 trillion. Add provincial debt: $800 billion. Congratulations! Your government owes over $7 trillion—approximately 2.5 times the size of our entire GDP.

And then there’s the shrinking workforce. Once, there were five workers per retiree. Soon, 2.5. Unless we start raising kids like veal and putting them to work at 14, there aren’t enough people to carry the burden. Cue rising taxes, declining services, and politicians calling it “resilience.”

So what’s the solution? Growth. Not a magical stimulus growth from a government program named after a squirrel. Real, sustained, adult growth. Growth that compounds. The kind of growth that allows the next generation to be so rich that they can afford to pay for our hip replacements with Bitcoin.

But oddly, none of our political parties seems particularly interested. They bicker over temporary blips, arguing about fiscal policy the way drunkards argue over cab fare. Yet, in the long term, the real issue is treated like a tedious uncle at Thanksgiving: nodded at, then ignored.

And it’s not like we don’t know the culprits. Our productivity is suffering because our investment levels are abysmal. Gross fixed capital formation—the adult term for “actually building something that lasts”—has fallen off a cliff.

From 2011 to 2015, we ranked 37th out of 47 OECD countries in investment growth. From 2015 to 2023? 44th. Ahead only of South Africa, Mexico, and Japan. That’s like bragging you outran a glacier.

Ten years ago, Canadian investment per worker was 95% of that in the U.S. Now it’s two-thirds. That’s not a decline. That’s surrender.

And what little investment do we have? Poured into housing, not productivity. Since 2000, investment in residential structures has doubled. Investment in machinery and equipment—you know, the things that help us produce things—has halved.

So yes, maybe we should ask: Are we a serious country? Or just a mortgage cult with a maple leaf?

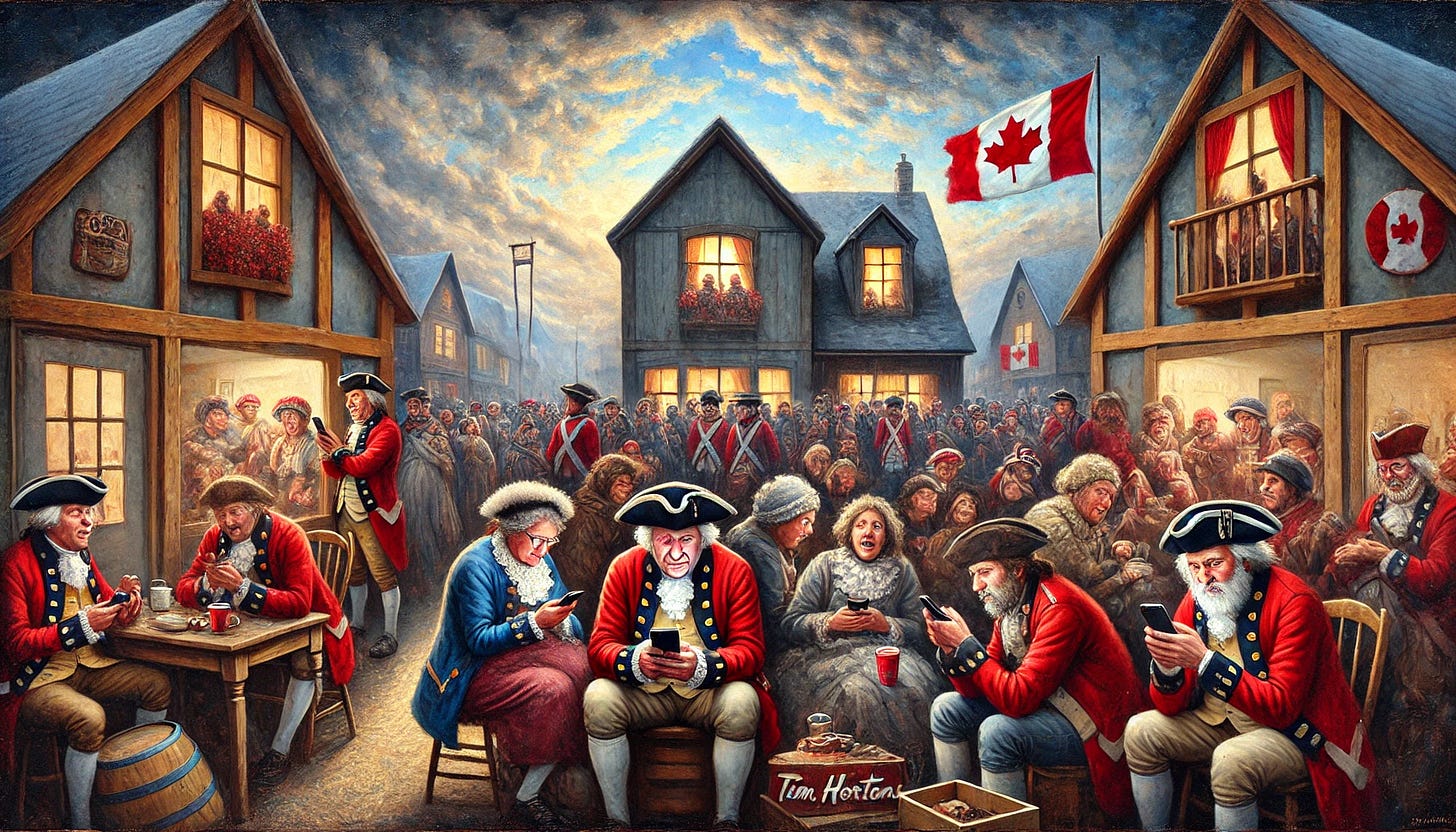

This is a picture of my puppy. Not relevant. But a puppy picture may help pull you out of the depression this article may have caused. Prosac sponsors this post. No, they don’t, as if I could get a sponsor.